A Conversation with Bill Plympton

Bill Plympton has undoubtedly been one of the hardest-working independent animators for the last two decades. Accompanied by an established career animating in his instantly-recognisable signature style for commercials, music videos and all manner of bumpers, promos and idents, he has also self-produced forty short films (including the Oscar-nominated “Your Face” and “Guard Dog”), written and directed five animated features and recently penned his first autobiography “Independently Animated”. A notable presence at this year’s Stuttgart Festival of Animated Film, Bill hosted the screenplay workshop “Adventures In Plymptoons” with his latest film “The Cow Who Wanted To Be A Hamburger” also screening in competition. I was privileged enough to sit down for a chat with him on life as an independent, his new book and what to expect from Plymptoons in the near future.

Was the workshop you presented this morning something tailored specifically to this festival, or is it something you tour with regularly?

Was the workshop you presented this morning something tailored specifically to this festival, or is it something you tour with regularly?

I do a lot of what I call ‘ master-classes’, I’ve done them for Pixar, Dreamworks, Disney – all over the world. This one was a little different in that it was advertised as being for screen-writing. So I modified my talk more in terms of how I tell a story, how I storyboard, how I design the characters. It’s a little bit of a different slant than my usual talk, but I showed films, some of my new projects, talked about how I developed the stories for them, and then I did some drawings, showed people how I create my characters. So it’s kind of essentially the same but with more of an emphasis on screen-writing.

Would you say that events such as this festival are important for up-and-comers, for developing their careers and networking?

Yeah, I believe that festivals are essential for my business and for anybody who’s starting out as a student or starting out in animation, because it’s here that they connect with all aspects of the industry. Whether they’re distributors, advertisers, acquisition people, press or other filmmakers, they can discuss ways to develop their talents and develop their sales. So the festivals are essential for getting the word out and connecting with the animation business. Stuttgart is one of the best festivals for that, really good for young filmmakers to meet other young filmmakers, to meet professionals and meet the industry.

It certainly does seem like, between your projects and festival appearances, you always have a bunch of plates spinning. Is there any one project at any given moment that you put more of a focus on?

Well, certainly the feature films are my main focus because those are the big projects that attract a lot of attention and hopefully attract a lot of money. Right now I’m talking about Cheatin’, which is my new feature film I’m about a third of the way through animating. Then I talk about the shorts, I’m working on a new dog film, my fifth, called Cop Dog. That’s important but not as important as the feature film.

It’s remarkable that, under ‘Plymptoons’, you’re able to find the time to not only produce such a multitude of short animated films, but also take on feature film production. Would you consider ‘Plymptoons’ to be a studio at this point or is it more of a brand?

It’s a brand, I think it’s important that it’s a brand. People know when they see a ‘Plymptoon’ what to expect – wild, surreal humour; a little bit of sex and violence; good drawing and craftsmanship; no computer animation. I think those are the ingredients of the brand and I think I’ve built up an audience now, a pretty good audience. People know me, although what’s really interesting is I’ll say “I’m Bill Plympton” and get “Oh, I don’t know who that is” – they’ll see a film and say “Oh, you’re that guy!” or “You’re the guy who does the surreal, coloured-pencil stuff”. So it is an identifiable brand, but oftentimes people don’t know my name. That’s my lack of marketing skills; I should have a promotions budget, I should have advertisers, promoters, but I don’t. That isn’t my primary goal, to promote my name – my primary goal is to make good films. And when you make good films they promote themselves.

I think that, within the UK at least, a major point of reference when referring to you and your style would be the ‘Nik-Nak’ commercials you worked on over here. People generally remember it instantly.

That was a huge campaign, a lot of money. In fact it was wonderful, they flew me to London to work on it and everything. So yeah, in England that’s where most people know me from are the ‘Nik-Nak’ ads – unfortunately. I wish they knew me for my feature films and my shorts but it’s mostly the ads. I think a lot of people over the world know me from MTV, and that’s where the ‘Nik-Nak’ people came to me, from the MTV stuff. So I think MTV and ‘Nik-Naks’ are the two big ones.

I’m curious about the book you just released, mainly as to how it came about. Were you approached to write it?

It’s an interesting story – I’m friends with Ralph Bakshi and we were at the San Diego Comic Con two years ago, he was promoting his book Unfiltered (Rizzoli, 2008). So we started hanging out, we went out drinking and he brought along his editor Robb Pearlman. We got kind of drunk and I think it was Ralph who said “Y’know Robb, you should do a book on Bill, he’s a good animator” and Robb agreed. So it was from that ‘meeting’ that we decided to do the book. Everybody started getting excited and, quite frankly, the book is selling very well, it’s getting amazing reviews. I think they were surprised at how well it’s done, because I’m not as big as Ralph Bakshi, I never had the big distribution – I mean, his films were all over the world in all the big cinemas; mine are very marginal I guess, they’re not wide releases or big DVD releases. I’m more of a cult figure as opposed to Ralph Bakshi, who’s more of a popular artist. So they’re very happy and we may do another one. I’ve got so many ideas for more movies and projects I want to do, so it’s not a capper of the career. Hopefully it’ll continue and I’ll do bigger things and bigger books.

The other thing that I loved about the book was how it’s really an art book as well as an autobiography. Were you involved in the layout at all?

No, that was all Chris McDonnell, who’s a young guy, an artist and cartoonist and he also laid out the Ralph Bakshi book. He just came into my apartment for two weeks and he said “Show me everything”. I brought out boxes of books, art, strips, a lot of stuff nobody’s ever seen before, that I did just for myself and put away. So that’s what’s so cool about the book is – like, the Madonna sketches, Madonna was the only person who saw them, so it’s nice to finally get that out and show the world some of these things that I did.

One of my favourite books on animation in the last few years is “Your Career In Animation” by David B. Levy, and I was quite happy to see his name attached to your book. What sort of level of involvement did he have?

Well, that’s another interesting story. There were actually two people I was considering, David and Amid Amidi. Amid is a very good friend of mine, he’s the co-creator of Cartoon Brew and he did a wonderful book called Cartoon Modern (Chronicle, 2006), all about UPA and all of that fifties deco style. So it was down to those two guys to co-write the book, and then Amid got this gig with John Kricfalusi for a bigger publisher. So David did it and I was fine with that, David’s great, a very good writer. I would write down the manuscript, relate all the stories I could think of, all the interesting stories. I really wrote a lot of stuff, like, fifty-thousand words I think. David would polish it and he didn’t do much editing, he would just smooth things out and restructure. Then he would send it to the editor Robb Pearlman who would say what could go or what wasn’t relevant – like, I’d talked about going to see Led Zeppelin and how it changed my life, y’know, and they said “No, Led Zeppelin – people don’t want to read about that”. So that was cut out, and other little things like that. They streamlined it a lot, and David was very good in terms of the structure, syntax, spelling, punctuation, giving things a nice flow to them. At the end of the book I wrote down my favourite films and my favourite film-makers, and I wanted to put my least favourite films, film-makers who I think are totally overrated and have no talent. David and Robb were totally against it, they both said “No, don’t do that, it’s a downer! People don’t want to read that”. I said “No, if I’m reading a book I’d want to see what not to see, what’s really bad”. I think it’s fascinating to see really terrible films, like The Chipmunk Adventure (Janice Karman, 1987) which I’d worked on, actually. Or something like The Black Cauldron (Richard Rich, 1985) or that Warner Bros. film Quest For Camelot (Frederik Du Chau, 1998). Terrible film, really bad, and I think that it’s important that people know that these films are not to be seen.

So, do you find that you encounter many other filmmakers who are a little fragile when it comes to ego and needing to have people like their work?

Yeah, ego can be a very dangerous thing. I think it’s important that you believe in yourself and you have faith in your talent, but some people think too much of themselves. I think I talked about Tale of Tales (Yuriy Norshtern, 1979) – they say it’s the best film ever made and I think that’s really dangerous, to say you’re the best film-maker ever. And if your ego gets too big, you lose sight of humility, you lose sight of learning, you lose sight of trying to make each film better and trying to better yourself; you think “I’m already there, I’m a genius, I don’t have to work any more”. So it’s really a danger, and I’ve seen a lot of people crash and burn because their egos are too big.

Something you hope for when reading about people you’re a fan of is learning things about them you didn’t know before. I had been completely unaware of the spate of live-action films you’d made in the nineties…

Mm, yeah, a lot of people are – ‘cause those films were total disasters! I released Guns on the Clackamas (1995) on DVD last year, and it got some good reviews but it didn’t sell very well. So the live-action was sort of a misguided step into Tim Burton territory, and I just don’t have the money to compete with the special effects films and the really surreal films by Terry Gilliam and people like that. I realised that if I’m gonna self-finance my films, I should probably stick to animation. It’s cheaper, it’s more what I know. I can do crazy, surreal things with animation that I can’t do with live-action.

As well as the book I’m also interested to see Alexia Anastasio’s upcoming documentary on your work, “Adventures In Plymptoons”. How did you two meet?

Well, she was an assistant to Esther Bell, who’s an old friend of mine and a wonderful, really talented filmmaker. I think Esther wanted me to do a cameo in one of her films and Alexia was there. She apparently didn’t know my work that well, so she asked me if she could look at one of my films and I showed it to her. This had to be, like, ten years ago, a long time ago. Then I ran into her at Sundance, they were at Sundance promoting their films, and I’d keep bumping into her. Finally she started talking to me about doing a documentary, and so she started shooting about two years ago. It’s nice that it’s finally done and it’s finally getting finished. There’s some crazy stuff in there, really neat stuff in there.

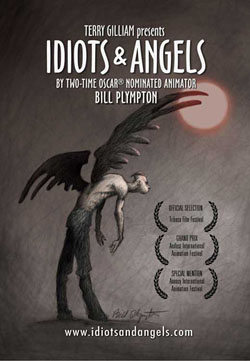

“Idiots & Angels” has been performing very well, do you feel it really ticked all the boxes you’d hoped to when you envisioned it?

It’s the most ‘Plympton’ film, I think, it really is. All hand-drawn, there’s no painted cels or anything like that. The drawings really come through, the humour is very ‘Plympton’…it’s a little more mature than my other films, more of a morality tale, more mysterious and just more magical than my other stuff. It’s my biggest success so far and it’s coming out on DVD in two months. In fact we’ll be presenting the DVD in Annecy, so we’re very excited about that. We think it’ll sell well.

Also unique in that it’s your first feature with no dialogue, is that right?

No dialogue. Music by Tom Waits and Pink Martini and Nicole Renaud, a lot of great music.

Do you find that it’s easier working without dialogue?

Yes, for a number of reasons. One is you don’t have to do a lot of translation and subtitling and dubbing, which is a big expense. Secondly, animation is a lot easier when you don’t have to worry about lip sync, which is very time-consuming and rigorous. Thirdly, I think it makes for more poetic storytelling, it’s more visual, it’s more visceral, you feel more intimate with the characters when you just see their eyes and you tell the story with their emotions, the way they move and the lighting. It’s more subtle, that’s why I like it.

You’ve published the storyboards for a couple of your other movies as books, is there any inclination to do a graphic novel adaptation of “Idiots & Angels”?

Yeah, we have the storyboards, just like with Hair High (RBM, 2003). I’ve been so busy doing the animation that I haven’t had time to put together a book, but it’s really something I want to do. It also takes money I don’t have to invest in making it, but that is the next step, is to definitely put it out as a book. Also we have a great soundtrack CD, and again I just haven’t been able to follow through with all the contracts to put out the music.

It certainly does sound like a good group of artists to associate with and to really contribute to that ‘Noir’ feel. Was it the first time working with those musicians?

I’ve worked with Nicole for a long time, I’d worked with Pink Martini, they’re an Oregon band – my brother’s in the band actually, and that’s one of the reasons I was able to get their music. But Tom Waits I‘d never worked with before, and what happened was I did something that’s very dangerous and should not be done, and that’s listening to music that you like while you’re drawing, because all of a sudden your brain starts connecting it with the animation and you get seduced into wanting that music for your film. Well, I did it and I got seduced! I don’t know Tom Waits, never met him, but I do know Jim Jarmusch and so I called up Jim and I said “I wanna send you a rough cut of the film. If you like it, pass it on to Tom Waits and see what he thinks”. I didn’t hear from anybody for a month, then I got this wonderful email from Tom’s wife saying “He loves the movie, you can have any song you want”! So Tom was really great to work for, he cut his price down to my budget – I can’t tell you what it is simply because he would get in trouble for saying this, but it really was very easy to work with him. He’s a very nice guy, not cut up in the Hollywood lifestyle, he just wants to do good work and see other people do good work, I think that’s really cool. For example, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (Terry Gilliam, 2009) – I mean, he was great in that, and he did it because he loves Terry Gilliam, he’d like to do something interesting and something fun, and that just says a lot about Tom Waits.

You mentioned before you’re working on this new film, Cheatin’. Is that all under wraps at the moment?

No, not at all. The music will also be by Nicole Renaud, I’ve got about a third of it done. It’s looking really good, people really respond to the pencil tests that I’ve been doing. I may start releasing clips of the pencil tests online, just to get people excited about it. I’m hoping to finish it in maybe two years, and bring it to – well, I dunno, Cannes or Toronto or Sundance, try and get a big release out of it.

Looking at some of the early sketches in the book, they’re very recognisable as yours but also kind of veering in a different direction.

Uh-huh, a lot more exaggerated, a lot more stylised, distorted, which I’m really excited about.

Was there more of an influence of older artists such as Charles Addams?

Not Charles Addams, though I love Charles Addams, especially his humour, his weird, dark gags. If you want to find an influence, look at Oscar Grillo or Carlos Nine, two wonderful Argentinian artists. Those are the guys who are influencing me on this one. Idiots & Angels, the influence was actually more Charles Addams and Roland Topor, but the new film is really more extended and exaggerated physiques. I wanted to experiment more with that stylised, stretched-out anatomy.

Your latest short The Cow Who Wanted To Be A Hamburger is, comparatively speaking, quite family-friendly. How did the film come about?

I’d gotten the idea three or four years earlier when I was in Oregon, and I saw these cows grazing. They wouldn’t be interrupted for anything, trucks would scream by and they were completely oblivious. It was as though they were trying to make themselves steaks as fast as they could, and it seemed like a funny idea for a film – The Cow Who Wanted To Be A Hamburger. It sat in my brain for about two or three years, and last year when I was teaching a school of animation I thought “Why don’t I bring that funny title out and use it as a teaching tool, as an example of how I make my films?” The first week was to write a story, second week was design the characters, we would do a storyboard and so on, and the whole film was the result of a three-month process. But at the last class the ending didn’t work, nobody really responded to it. I said “C’mon fellas, help me out” and they pointed out that the mother cow was really central to the story, but I’d neglected her in the end. I think the ending I’d had was something like, the cow pushes the butchers into the meat grinder and the last shot is the cow eating a butcher burger. They didn’t like that ‘cause, I dunno, it was too gross I guess. So I figured “You’re right, I should bring the mother cow back and have her character resolve the story. People like that ending, it’s a lot more sentimental, it’s a lot more evocative, it’s a sweeter story and people really, really dig it.

Clip from “The Cow Who Wanted To Be A Hamburger:

You’ve mentioned elsewhere that you had wanted it to come off as a children’s fable of sorts, do you consider it a morality tale?

There’s three or four messages in the film; The power of advertising; the meat industry; the power of a mother’s love; and, oftentimes, what you really want so badly isn’t necessarily such a good thing. I don’t usually have strong messages in my films. The class wanted me to talk about issues and talk about philosophy and deeper meaning, because usually I’m just a joke guy and hope to make people laugh. Actually, the Cow film is not a funny film, there’s a couple of gags like when he’s exercising, but there’s not a lot of laughs. It’s ‘sensitive’ Bill Plympton, which is kind of strange.

Like with “Idiots & Angels” it seems that the music drives the story in a way.

Like with “Idiots & Angels” it seems that the music drives the story in a way.

There’s no sound effects in the film either, mainly because I was really broke and couldn’t afford a sound effects person, so I asked a musician to give me some musical sound effects. That’s been done before, Peter and the Wolf (Sterling Holloway, a1946), the old Disney film, all the characters in that had musical instruments to portray their personality. So whenever there’s sound, you’re hearing a trumpet or a flute or something like that. And I liked that, I thought it worked really well.

I get the impression that, when working on your films, you’re not entirely on your own, that you do have people supporting you and helping out. Do you have a regular staff at this point, or do you bring on freelancers to help out?

I have an office manager who runs the shipping of the prints, all the business of billing and payroll and that stuff; then I have a producer, Desiree Stavracos, who runs the website and editing and all the production stuff; and then I have an artistic supervisor, she runs colouring and other artistic things. But it’s still basically just me doing the story, storyboards, character design, animation, pencil tests, backgrounds – then once all the artwork is done I give them to my crew, Desiree and Lindsay (Woods), and they put it all together. I do have some interns come in occasionally to help out, but basically that’s it, four or five people at most.

That way you get an end product that’s quite true to what you originally had in mind?

Yeah, it’s really just me working by myself, with them helping me put the film together. I don’t want to get bogged down in bureaucracy, meetings, a big staff of people. If I was doing a huge production I would probably have to, but I like keeping the films small, intimate, personal. I just like that feeling.

Where I’m from, people seem to have a rough time making a film off their own back. There’s an expectation, almost, of going through the process of finding funding first, or approaching a scheme, even if that means losing creative control. I would assume that you would probably rather stick with what you do of producing films on your own steam, keeping them the way you want and recouping the cost once they’re finished?

Well, one of the things I talked about this morning were these rules I call “Plympton’s Dogma”, and these are my three rules for becoming successful as an independent animator. Rule number one is make your film short – five minutes or so; rule number two is make your film cheap, roughly a thousand dollars a minute; Rule three is to make it funny. If you can follow all three of those rules, your film will probably be a success and will probably make money. I judge a lot of festivals, and when I see a film is twenty minutes long I already don’t want to watch it, because if it’s a bad film I’m stuck with nearly half an hour of crap. So the rules are available to anybody. Another American animator, Don Hertzfeld, he’s extremely successful as an independent. His films sell all over the world, especially the US. In fact he’s much more successful than I am, because his films are so damn funny. So it is possible to not have to go to these grants and big corporations looking for money and trying to sell an idea. I think if you follow my dogma you can be truly independent, make your own films and make money.

Bill’s short “The Cow Who Wanted To Be A Hamburger” won the Special Award for Best Music in an Animated Film at Stuttgart. He is also presenting his latest award-winning short “Guard Dog Global Jam” at festivals all over the world, and his most recent feature “Idiots & Angels” will be released on DVD in June. More info available at plymptoons.com and idiotsandangels.com

“Idiots & Angels” Teaser: