Q&A with Howie Shia (‘BAM’)

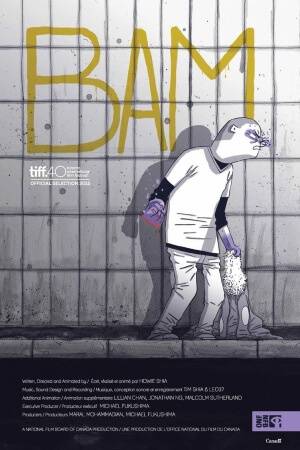

Toronto-based Howie Shia’s work as an animator, illustrator and director has seen him creatively involved with clients including Disney, Nike and Freemantle. A co-founder of production company PPF House alongside his brothers Tim and Leo, Howie has also channeled his creative energies into a series of personal films. His fourth animated short produced with the National Film Board of Canada is BAM, following on from Ice Ages (produced as part of the NFB’s Hothouse apprenticeship scheme) Flutter and Peggy Baker: Four Phrases. The film takes the audience on a journey of the life of a studious and introverted boxer who fights an ongoing battle with his own psychological demons and propensity toward bouts of violent rage. With festival screenings including the Toronto International Film Festival at which it premiered and the upcoming Sommets du cinéma d’animation in Montreal, Skwigly were keen to learn more about this thoughtful, arresting and extremely well-designed new film.

For the production of Ice Ages you were involved in one of the earliest editions of the NFB’s Hothouse apprenticeship scheme. Was it this involvement that began your association with the Film Board?

My first experiences with the NFB were actually with the Toronto documentary studio. A couple of years prior to my applying to Hothouse, I had received a grant from their Filmmaker’s Assistance Program to help finish a short experimental doc I was making about Antonin Artaud. That led to my meeting then-NFB-producer Karen King, who gave me an internship on a documentary feature called Film Club, by Cyrus Sundar Singh, and a few other odd jobs both on set and in the office. I found out about Hothouse during that time and applied and was unexpectedly accepted.

Were there other major benefits to your involvement in Hothouse, from a creative/artistic standpoint?

There were two major ones that I can think of. Firstly, I learned how to animate. Hahaha. Seriously, I had worked primarily as an illustrator and a video artist prior to Hothouse. I had done some very crude animation in a number of my videos but I had never actually learned how to animate. And then suddenly I’m in a studio full of some of the world’s greatest animators. I learned about everything from squash and stretch to how to use After Effects.

Secondly, being at the NFB animation studio in Montreal, you really get to see animation happening in all its various forms—from cel animation, to cut-out, to stop-motion, CG, stereoscopic sky-drawing (google “SANDEE”), scratching on film, painting on glass… one of the other Hothousers, Megann Reid, was animating with honey—who knew you could animate with honey? And while that’s all fancy and fun in and of itself, there’s actually, I think, a larger lesson to learn, which is this: I think a lot of people—myself included at that time—think of animation as an aesthetic or a set of aesthetics: anime versus Disney versus Henry Selick versus etc. But being literally the most junior animator in the whole building, spending time with people like Michael Fukushima and Janet Perlman and all of the other animators at the NFB, I began to pick up on this idea that maybe animation is an end in itself; that putting down a thought and advancing it one frame at a time is its own sort of music that has nothing to do with the cosmetics of animation. Regardless of what story—or non-story—they were telling, and regardless of what specific medium they were using, all of the animators at the NFB were committed to this very beautiful and stupid idea of breaking down a moment into its component parts and putting it back together again—but maybe with a little push here, or a little stall there.

Can you describe your creative background up to that point?

I was a graduate of the U of T Visual Studies program, studying under George Hawken, Colin Campbell, Kim Andrews, Lisa Steel and Kim Tomczak.

After university, I worked primarily as an illustrator and video artist and secretly made comic books and wrote screenplays on the side. Eventually, my brothers (both musicians) and I started a studio, PPF House, which makes music and videos (both as independent artists and as freelance contractors).

What were the circumstances that led to your latest NFB production BAM?

I had spent much of the previous five years developing shows for Disney and while I quite like that work—it’s fun and a good muscle to exercise—by the end of it I had started itching to doing something more personal again, something that I could really control every frame of. I started talking to Michael Fukushima (Executive Producer of English Animation at the NFB) about working together on something again and luckily, just as things were winding down with the mainstream work, there seemed to be an opening in the programming slate at the NFB. Michael was interested in some of the stuff my brothers and I were doing together in combining music and animation, so he suggested I put a pitch together that had a heavy music component.

For a long time my older brother, Tim (who co-wrote the score), had had this idea of taking the old Hanna Barbera shtick of playing drum solos behind fight scenes and trying to make it actually emotionally engaging. At the same time, I had always wanted to make a film about boxing. BAM was the result of all of that.

Interspersed throughout the film are images of Greek Gods overseeing the events as they play out. What do these represent to you?

Harry, the protagonist of the film, is a bookish, mild-mannered kid who just so happens to have a profound instinct and talent for violence. Today, that combination of thoughtfulness and physical power seems unlikely, even contradictory, but the partisan politics of lovers versus fighters that Harry struggles with doesn’t exist for the classical heroes that populate his book collection. Odysseus, Beowulf, Zatoichi, Batman—all of them are brilliant and sensitive; all of them are bruisers. By mythological standards, Harry is really quite a normal hero doing exactly what he should be doing. The problem is that he doesn’t live in the mythological world.

I think (I think) the Gods in the film are a manifestation of that idea. Subjecting classical archetypes and values to contemporary judgments was a way to explore the broader cultural and literary context of Harry’s condition.

The film reportedly draws from recollections of your own grandfather. Can you expand on how and to what extent his life had a role in the film’s story?

Again, it comes down to that false dichotomy we live with today, of lovers vs. fighters. My grandfather was both a high-ranking police official in Taiwan—a brutal man by occupation—but also a revered calligrapher and poet. Whenever I tell people that, they tell me how strange that combination is, but really at that time, in that place, I don’t know that it was. BAM comes largely out of a question about who my grandfather would be if he was growing up today, subjected to our modern judgments and definitions. Would he have to choose between his physicality and his intellect, and what do you do with all of that power if you have no wars to fight and no dragons to slay?

Was there any other research into the psychology and physiology of uncontrollable rage when developing the film?

Hmmm… no. That probably would have been a good idea. Haha. In the end, I think I was ultimately more interested in rage as a problem versus rage as a phenomenon (if that makes sense). What I mean is that, for example, I’ve read articles about the chemistry of love and infatuation, it’s fascinating stuff and does inform my experience and discussions of it, but ultimately it doesn’t help when coping with a broken heart—whereas a love song, somehow, does.

The film features music from your brothers Tim and Leo, do you often collaborate together on creative projects?

Yes. Our parents force us to. Haha. In fact, it really is something we’ve done ever since we were, well, alive: tell stories, play in bands, make films—although it wasn’t until after university that we made it official when we started up our studio, PPF House. Now we do a lot of each other’s independent projects but help out on contract work. We’ve done stuff for Disney, Nike, the CBC, UN-Habitat, lots of different clients. We’re mostly based in Toronto and Taipei but also spend a lot of time working with musicians and artists in New York.

Interestingly, the protagonist’s temper seems to be represented not by the colour red but purple. Can you describe what went into the development of the overall palette used in the film?

I started out wanting the film to feel like the drawings I had just started exploring in my sketchbooks—experiments combining ballpoint pen and Chinese ink wash and brush pens. Filmmaking vocabulary all seems so epic these days, I think what I liked was the theatre of telling a very big, dramatic story using a very limited selection of basic tools.

The idea of avoiding red specifically came from Michael Fukushima, who suggested it was a little cliché. That led me towards finding a softer, less obvious colour that might help remove the automatic associations that come with a red rage—machismo, vitriol, bloodlust—and allow us to look at this thing a little more scientifically: What exactly is this thing that takes over when we tip over into violence? Does it have a purpose? A moral? A gender?

As with Flutter, a major component of BAM’s initial atmosphere is a gritty, urban backdrop. Does this type of environment have particular resonance for you as a visual artist?

I think much of my interest in urban settings is actually a symptom of my love for classical mythologies. I respond really strongly to the primordial poetics and rituals of old myths and I like digging through the civility and technology and politics of modern cities to see if you can still find traces of those ancient stories in the scaffolding. Is there a relationship between the primordial melodrama of, say, on the one hand, Atlas struggling beneath the weight of heaven and, on the other, that exquisite mundaneness of Prufrock measuring out his life with coffee spoons?

On any given day on the subway you can find yourself sandwiched between, on the one side, a twitchy 20-something telemarketer who lives entirely for Instagram, and on the other side, a hard-ass immigrant grandmother whose entire day is spent appeasing superstitions from the old country. And both of them have the newest iPhone. I like exploring the space in between those two people.

Flutter also seemed to deal with the theme of escape, would you say in certain respects this is also the case with BAM, in the lead character’s struggle with himself?

That’s a good question. In fact, I think it’s possible that the boxer actually resents the notion that his violent streak is a flaw—certainly it’s not for the heroes of the stories he reads and certainly it has provided for him in its own way. There’s no doubt that he is frustrated by the fact that the world around him judges him for his temper, but whether he means to escape that world or pound it into submission is hard to say for me.

If I’m not mistaken, Flutter was largely (entirely?) animated in Photoshop. Was this also the case with BAM or were there other software/process used this time around?

Yeah, Flutter was all done in Photoshop, just by clicking layers on and off really fast. I didn’t know how to get the lines and textures I wanted otherwise. This time around, luckily, there was TV Paint, so production was really straightforward: I did rough boards in Photoshop and animated in TV Paint. We did the film in 4K so the drawings had to be huge and took a long time to do (TV Paint drawings are in pixels, not vectors, so you can’t just scale up and down) but it was worth it for the line quality and texture we got out of it.

All of the backgrounds were drawn in ballpoint pen and Chinese ink wash (I grind the ink out by hand) on a really interesting paper called Terraskin, which is made mostly of calcium carbonate and has the amazing feature of not buckling under water.

Everything was composited in After Effects and cut together in Premiere.

Do you have any future plans as far as what you wish to do with BAM now that it’s out there, or any other creative projects on the boil?

Well, I hope BAM has a healthy and successful festival run. It was made in 4K and has a gorgeous 7.1 Dolby mix so it’s really meant to be experienced in a theatre. I’m also starting work on a graphic novel that is a sequel of sorts to BAM—about the next generation, as it were—that is both much longer and quieter than its predecessor.

Other than that, I’m at the beginning of a whole bunch of things: I’m developing an animated kids’ adventure series for TV; a YA graphic novel; and PPF has just started working out an online animated project set in the Taipei hip-hop community.

BAM will play this week in Montreal as part of the Panorama Québec-Canada of Sommets du cinéma d’animation on November 28th alongside other recent NFB productions My Heart Attack (Dir. Sheldon Cohen) and All The Rage (Dir. Alexandra Lemay).