London Film Festival 2018: Animation Report

Animated films were sprinkled like gold dust across this year’s London Film Festival programme. The fact that they were grouped with live action in themed strands, rather than ghettoised in their own sidebar, was encouraging. Yet there was one screening that animation dominated: Amazing and Astounding, a grab bag of surreal shorts which explored aberrant dreamscapes and psyches. Perhaps animators are still best placed to explore the farther reaches of the mind.

The screening started strong with Hungarian animator Réka Bucsi’s Solar Walk, the only animation in the festival’s shorts competition (and a hot Oscars contender). Two homunculi board a rocket built by alien marsupials. This is Bucsi’s cue to unchain her subconscious: men, marsupials and other benign creatures journey through varyingly abstract scenarios linked only by a loose theme of friendly cooperation. The quaint futurism evokes the late Roger Mainwood’s Autobahn (1979). Like that film, Solar Walk was conceived as an accompaniment to a musical composition – in this case, an orchestral jazz piece (the 21-minute work I saw is a festival cut). Music is indeed an apt metaphor for the intuitive way in which its narrative unfolds.

Bucsi’s animation, a mixture of 2D and 3D, soothes with its sinuous forms and pastel palettes. In contrast, Nikita Diakur’s Fest revels in its crudeness. It is, after all, a follow-up to a short called Ugly. Like that film, Fest exploits glitches in the Cinema 4D software to create an irrational, disjointed CGI world. A pack of ravers wigs out to techno in the street while a bungee jumper prepares to leap from a nearby tower block. But the models are malformed, the texturing is all wrong, and one character randomly explodes into a mess of pixels. CGI is generally used to generate slick, even realist animation. Diakur bares the technology’s nuts and bolts, showing us that it is as artificial, as fragile, as any other animation medium.

Equally self-reflexive was Inanimate, Lucia Bulgheroni’s Cannes-winning stop-motion short. A woman’s comfy bourgeois life is disrupted by terrifying lurches through space and time. Eventually, the camera rises to reveal the animators at work in the studio; we realise that the lurches correspond to the puppet’s transitions between sets, of which she has grown conscious. The glassy-eyed clay figures and mood of psychic disturbance bring Anomalisa (2015) to mind. The film is let down by mannered voice acting, but I was gratified to see an animator think outside the box – literally.

The other shorts were less striking, but programmer Philip Ilson (of the London Short Film Festival) did well to sustain the theme of disorientation across stylistically disparate works. I can’t account for the programme’s inclusion in the Thrill strand: my experience wasn’t so much edge-of-seat as out-of-body.

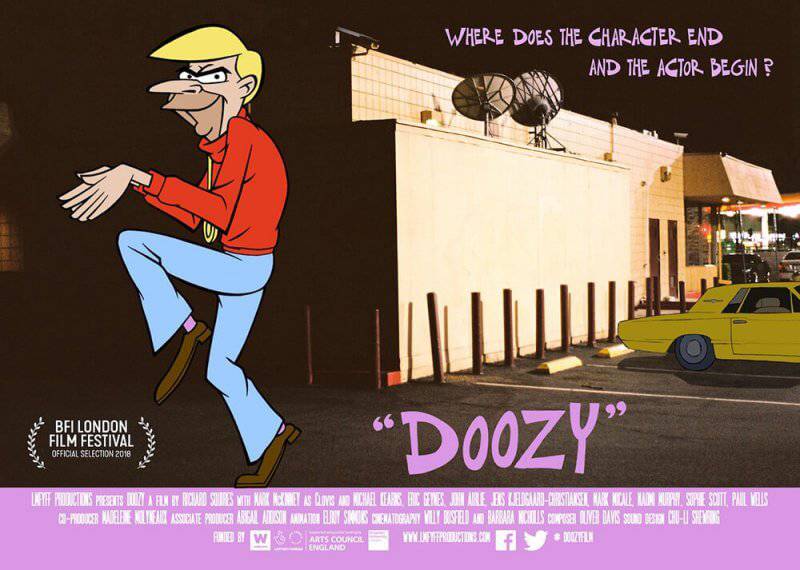

Elsewhere at the festival, animation was predictably concentrated in the Family programmes, with several exceptions. One was Doozy, a curious hybrid documentary by London-based artist Richard Squires. The feature premiered as part of the Experimenta gala, yet while its approach is unorthodox, its subject is one of the most mainstream cartoon studios of all time.

Hanna-Barbera ruled the airwaves throughout the 1960s and 70s. The American powerhouse pioneered cut-rate animation methods, resulting in a crude visual style much mocked by its competitors; it compensated with sharp scripts, delivered by a roster of star voice actors. Most infamous was the comedian Paul Lynde, whose roguish TV persona riffed on his barely concealed homosexuality. He became Hanna-Barbera’s villain of choice, lending his trademark nasal vocals to such dastardly creeps as Mildew Wolf (It’s the Wolf) and Templeton the Rat (Charlotte’s Web).

Squires grew up with Lynde’s catchphrases ringing in his ears. Only later did the artist detect something a bit off in the characterisation of these baddies. They were predatory, cross-dressing weirdos, bitter with thwarted desire – not far off gay stereotypes of the time. Lynde’s affected intonations completed the picture. Hanna-Barbera, it seemed, was leveraging the comedian’s reputation in the worst way. Squires’ inquiries led him to make his first feature, Doozy (a word Lynde delivered with extra relish).

The subject is a good fit for the director. His unsettling works, which range across films, comics and installations, are concerned with how repressed urges manifest in the body. In the animated short Francis, a child psychologist’s voiceover comments on the physical tics of a heavily autistic boy. The live-action The Pisser shows a boy squirming in discomfort, followed by a close-up shot of wee soaking his boxers.

Doozy plays it straighter. Squires weaves talking heads, mostly academics, together with audio recordings of Lynde in action. The scholars discuss the social cues contained in people’s vocal mannerisms, touching on why campness might have been associated with villainy. Occasionally, a cartoon avatar of Lynde – animated by Elroy Simmons as a cackling Hanna-Barbera-style villain – enters the frame to re-enact alleged scandals from the comedian’s past.

“Alleged” is the operative word. Lynde’s closeted life remains shrouded in rumour, and the filmmakers had to tread carefully to avoid libel. As a result, these animated scenes reveal very little; some barely make sense. Legal issues may also account for the lack of Hanna-Barbera clips – by and large, we only hear the soundtrack. In his introduction to the screening, Squires described the production as “traumatic”. This may be what he had in mind.

The talking heads give some helpful context to Lynde’s career. Yet the actor himself doesn’t really come into focus. Did he have any misgivings about his characters? Or, in the contrary, was animation a convenient veil behind which he could live out his personality to the max? These questions are never asked. Lynde is long dead; the only interviewee who knew him personally is an elderly ex-classmate, who seems touchingly oblivious to his sexuality (she fondly reminisces about a kiss they once shared).

One thing’s for sure: Lynde was a standout voice actor, at once affecting and cartoonishly wacky. For all its limitations, Doozy does well to spotlight a neglected aspect of animated films. It reminds us that voice acting is crucial, and an art in its own right. In an age when the big animation studios cast actors according to how famous they are, this needs to be said.