Interview with Director Michael Cusack

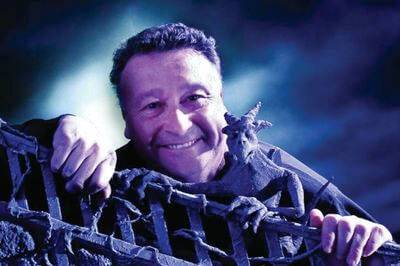

Michael Cusack is one half of stop-motion studio Anifex based in Adelaide Australia. With a career spanning over three decades, many of his short films have screened across the globe. Having won juries over in Germany, Canada, France and America, this small Australian company is doing its part to remind the world of Oz’s part in the animation community as a whole.

The company’s new short film Sleight of Hand is currently doing the rounds, grabbing up prizes and screenings in abundance. One of the greatest accolades so far has been the award to cinematographer Jo Rossiter for Australian Cinematographer of the Year.

One of the most noteworthy scenes Rossiter was responsible for include a 360° rotating shot where the set itself was set up to rotate during filming, requiring the lighting rig to move at exactly the same speed as the scenery. Such intuitive ideas are part of the reason why Cusack’s team are able to keep afloat in this economy.

Skwigly had the opportunity to discuss Cusack’s new film, his career and passion for all things stop-motion and animated.

How did you become interested in animation? What is it about stop-motion that makes you want to work in the medium?

Like most people, Ray Harryhausen was a huge influence. I can remember when I was very small kid, must have been about 7 or 8, my sister took me to the Broadway cinema, in Manchester for a matinée and it was Jason and the Argonauts. I was fascinated as child by monsters, seeing Jason fighting the skeletons and the Hydra just sparked something inside me. I didn’t know how it was done, I just remember really liking the Hydra I just thought it was brilliant. The next thing was seeing the original King Kong on television – that really piqued my interest. I was also really into dinosaurs, and my parents took me to see One Million Years BC with Raquel Walsh, in a rabbit-skin bikini. I was only about 9 then and that had really profound affect on me – she was fighting dinosaurs, it was just amazing!

When I actually started to animate properly I was doing a drama course at university in South Australia. I had every intention of continuing the course doing Drama and becoming a Drama teacher. The course was divided into two parts. You did drama and theatre studies for the first six months and then did screen studies in the other half. And because I was doing so much drama and theatre stuff outside of the course, all the course stuff was things I’d already done. So it didn’t really tax me and I didn’t find it very exciting. Then when it came to the second half of the course in Screen Studies, I’d never done anything like it before so when it came to the second year when you specialised in either Drama or Screen Studies, I chose Screen Studies because it was a bit of challenge. And I loved it. And it was there that I met my business partner Richard Chataway. This was in the late 70s so we’ve been working together for a very long time now. We decided we’d combine his love of all things technical because he was a theatre lighter, he loved cameras and digital photography. It seemed like a pretty good match as I’m technically inept, though I can sculpt so we decide to join forces and make a stop-motion film. Now I often say this and people don’t believe me, but part of the reason we did this was because we were a bit lazy and the idea of lugging around film equipment on the weekend was a pain in the bum. So if we could just set up in one room and animate in front of it and not move any equipment around it would be a score!

We didn’t realise how complicated it could get, so we began animating this short 3 minute film, which is absolutely, diabolically bad. But we fell in love with the whole concept. And then we saw some films by Will Vinton, especially his Oscar winning film Closed Mondays. That was a bit depressing because it was so good, and we thought we could ether give up or try to make something that good. So for our BA degree we made a 30min stop-motion film, which was a bit better than the first one – still pretty bad by today’s standards, but it was 26 minutes long because we didn’t realise it would actually take us long as it did. It became the basis for our thesis and then Richard and I were given our BA Degree. It was 99% pass mark, which at that time was the highest percentage pass rate achieved in the state and I think that was partially because people were amazed we were able to do it. One of the things we have taken with us is something our film lecturer said to us at that point, “The thing that you and Richard have got, is a factor called stick-ability. Once you’ve started something you’re like bull-terriers, you just hang onto it and keep at it until its done”. I think that’s very true, we’re both very, very driven when we start, we don’t start projects and not finish them off. I think for so many filmmakers starting out like we were then, if it gets a bit too hard – or a lot to0 hard – a lot of people bail, but it’s just not in our DNA. When we decide to do something it just gets done. By hell or high water it will happen.

I think people noticed that, so straight after university we were offered jobs at the South Australia film cooperation to start up their animation department, which was an absolutely astonishing stroke of luck. Whilst we were there we worked on a few films’ special effects. It was just animation back then, we also made a clay animation of Waltzing Matilda, a famous Australian song and that won the Australian Film Institute award for Best Animation. That was actually only the third animated film I’d done and winning that was quite special. We were taken to Sydney and put in a really swanky hotel overlooking Sydney bridge. We went to the ceremony that night and won, we were absolutely gobsmacked! Then we finished our two-year contract with the film cooperation, started our own company Anifex and we’ve been working as Anifex ever since.

As a company Anifex produces a lot of commercials with big names under your belt. How do theses commercial ventures compare to working on your own short films?

The thing about working on commercials is there’s normally the budget to try a few things out that we may not have been able to try out when its our own money. The first couple of films we made we got funding for but we found the influence of the funding bodies trying to make changes and do things a ‘slightly’ different way became a little bit abhorrent to us. I believe some of those funding bodies are better now, but when we started out they’d take your script, talk through it with you and try changing it to something they’d rather see as they’re putting the money up. So they became very much involved and I think when you’re making your own films it should be one person’s vision – the director’s – and we weren’t getting that.

What we did was take the commercial work we were doing, take a bit of the profit margin and put it to one side so when we had enough that’s when we’d make our own film. So the commercials were funding our short films. It also meant we weren’t then behove to what the funding body wanted, so we had absolute creative control over our own films. Which was wonderful.

The commercial side of things we call our ‘bread and butter money’ and the short films are ‘soul food’. As with an advertising agency, they come in with an idea with a script already written, all you can do is make suggestions about how it might work better but they might not take you up on that. As they’re paying the bill what they say goes, so artistically it’s nowhere near as exciting as the short films where every decision you make is yours, particularly the way we do them. By self-financing wherever we can it just means the film is your vision and not somebody else’s. This is the major difference between the two, the commercial stuff is still very good and I enjoy doing it, but I enjoy doing it for different reasons – I enjoy trying new things out that can perhaps then be used in a short film.

Your films have a real warmth and playfulness to them, where do you think this comes from?

That’s a nice question. I’ve been brought up in Australia and England for too long so it’s very hard to talk glowingly about one’s self but I do think I’m a reasonable, sensitive person. It especially surprised my niece the first time she ever saw Gargoyle. She came up to me and said “Uncle Michael, you have a sensitive side” – she was about 26 at the time! So it took her a while to realise.

I do really believe I have a sensitive side, I’m not afraid to say that I get involved when I watch films and programs, I can be wiping a tear away quite easily. I also think having a background in acting is very important as when you’re animating a character you are the actor and if you can’t understand what your puppet it supposed to be going through emotionally on the screen, you’re not going to get any kind of emotion out of the puppet at all.

I also think stop-motion itself carries a certain amount of warmth and pathos naturally with it, as it is so obvious when you’re watching it that there’s a human manipulating the puppet. I think that gives it warmth and a quality that other animation forms struggle to have. If you look at Wallace and Gromit they’re just lovely characters and everyone loves them. Everyone loves Shrek but I think in a different way, and I think the way people like the characters in Toy Story is because they look and move wonderfully. I’m not sure that it’s necessarily got a lot to do with their characters as with Wallace and Gromit, it’s all about character but I think that comes from the fact that they are stop-motion.

You mentioned Gargoyle before – it is a very tender film of lost love, is there a story behind the situation or was it completely hyperphysical?

No, Gargoyle has a very strong story behind it. I wrote it immediately after I found out that my Mother had cancer, and so it was very much a study on grief and loss. I hadn’t actually lost her at that point, she was still alive but certainly the prognosis wasn’t looking good and I was always was a bit doubtful that a film or a song or anything else could be really cathartic when facing a problem. I just really felt compelled to write that story and that’s why I think that when people watch it they get real sense of emotion coming from it, because it was really there. Stylistically it was a combination of things, I had recently come back from a trip to Paris and seen the gargoyles at Notre Dame and the town hall in Munich. It was also a throwback to my youth, of wanting to be moving around with monsters, so the film gave me another outlet to do that.

(R)evolution was a film that had a lot of humour to it as well as commenting on the way society works – or doesn’t work, in this case. How did the plot and design of this piece come together?

That was another weird one I got from an art gallery, I saw an alchemist painting from the 1400s and it just struck me that he was trying to create – in that case blood into gold – was a doomed activity that would never work – but what if it did? I’m very interested in fossils and evolution myself, so instead of a scientist trying to create gold from lead, what if the scientist tried to create life from snot? That’s why the guy sneezes on it as that’s the missing ingredient: mucus. From there the characters evolve very rapidly, starting off as two rolling blobs of clay. By the time they finish they’ve established religion for themselves and the two religions clash and they end up killing each other, so it’s a pretty unsettling message from that point of view. But it was a lot of fun to make, and it had quite a lot of relevance at the time it came out as there were – and still are – quite a few religious wars going on which I can’t understand at all, but they’re happening so we have to accept them.

The Book Keeper which was screened at Annecy, was this a story you’d been working on for a long time before production?

Actually a friend of mine is an author and he’d written a whole series of short stories that were published. I was talking to him one day and he said he had a story I might like. He sent it to me, I read it, thought it was actually really good and decided to make it into a short film. That was one of the first films where I had a problem with a funding body, because we needed some money to make this obviously large-scale project and hadn’t done a high amount of commercials at that point. As our ‘soul food’ fund wasn’t particularly flush with money we decided to get a grant, which we got but the grant body gave us a mentor who I think really wanted to be a filmmaker. He wasn’t really enamoured with the film I wanted to make and kept implying that if we didn’t make the changes that they wanted they would withdraw. Originally it had much shorter start to the film, which would have given me more time to play out the end of the film, so I think the film accelerates too quickly at the end of the film. It couldn’t be any longer than 7 minutes and I think I wasted a minute and a half that we didn’t need at the beginning which they insisted went in. Having said that, I still really enjoyed the film, because the majority of it is what I wanted it to be. I think it’s effective, and a lot of people like it. I still think it’s my film but it was from then on that we decided to self-finance.

Deane Taylor (art director on The Nightmare Before Christmas) was the art director on the film, how did you get him involved?

Dean did all the character and set deigns for us, he had just finished working on Nightmare so that’s why they all have that extraordinary, quirky look. He kept coming round, making sure we were being faithful to his designs and so on. I actually wrote the screen play with Strephyn Mappin who was the author of the original story and he was actually quite surprised when he saw the set and characters. He hadn’t stipulated as much in his story but he always saw the library as being all chrome and glass and white surfaces, and we took it in the direction of decay and bugs and wood – he was quite surprised to see that.

But once again he was very happy that his story was being made into a film at all. It was very interesting as he had written this short story and he was based in Victoria which is an hour away by plane so he wasn’t really involved in any of the construction side of thing but at one point he came over to have a look at sets and props just out of interest and I started showing him around. I was being reasonably offhand about it, “Here’s the main character, there’s the grandmother and the kid that tries to steal the book and so on”. And I looked at him and realised his eyes were welling up! Here I am, saying I think I’m a sensitive sort of person, but I hadn’t really taken into account that for him this was seeing his book come to life. He was quite moved by that and as soon as I saw that I immediately backtracked and was bit more careful and sensitive about they way I was presenting it to him, because of course he’d written this story and lived with these characters and then here they were coming to life in front of his eyes. I kick myself for not catching onto that earlier, as it’s a bit like when you make a film, present it to people and want them to like it. It may not be your motivation for making it but ultimately you don’t want people coming up to you and saying “I saw your film and was a heap of S**t”. And that has happened, but with him he just wanted time with the character and it to be explained to him properly which I initially I didn’t do very well, but by the end we were looking at everything quite reverently.

Can you tell us a little bit about the puppet fabrication at Anifex – is it all in-house or do you outsource?

We make everything in-house once again, this I guess part of being a directorial control freak. We used to send things out when we made TV commercials, but we found that we don’t have the equivalent of MacKinnon and Saunders in Australia. So we would send stuff out and people didn’t either put the love and care into them that that we thought was necessary or deadlines would be missed. It just got to the point where we thought, “To hell with this, we’ve got our own studio, let’s put a workshop in and make all the sets, characters and armatures ourselves”. That way as a director I can keep track of everything that’s happening. I can keep track of the characters and say “I need an extra joint here”, or “This character’s only leaning against a wall so doesn’t need a full armature”. Or the sets – I might say “That’s great but I can’t get to the back so I need a trap door to animate the character”. It became a lot easier to work, having everything built in house, as the workshop is literally a minute away and also if the model makers and sculptors have problem they can ask me straight away and we can fix it immediately. I know we’re unusual in having that capability but it makes the job a lot easier.

Your new short film, Sleight of Hand uses facial animation in a very interesting way, very clearly demonstrating stop-motion replacements. What was the reason behind this?

The motivation for doing Sleight of Hand came thick and fast, it was initially the result of animating at about 3 o’clock in the morning with a puppet for a TV commercial, and I though to myself I wonder if this guy has an alternative life, I guess a little like the toy box coming alive at night when you’re a kid. I wonder if this character thinks it’s in charge of its own destiny, that I thought was a really intriguing idea. So I started to play around with the idea of a character that believes he has free will but then discovered he’s got nothing like free will and I thought that was really powerful as well.

As I was writing the script a whole bunch of other ideas came in, the idea of playing with time, one of the clues to that is really early on in the film he takes out a watch and glances at it an then looks at himself in the mirror I thought that may give the audience a clue to what happens later when the forth wall brakes down and the vail is lifted and he can see he is merely a manipulated character and that there was a whole raft of activity between the frames that make up his life. For me one of the most poignant moments in the film is when he standing on the animation table just watching the animation counter go up, for him he’s just living his life at normal speed not realising that this entire sped up world is happening around him which is of course are world. It’s a reasonably complicated idea, especially to sell in 10 minutes.

The other point I really wanted to put across is that it was done in stop-motion as I think at this moment professionals, less so with students that still have very good access to do stop motion, but a lot of them are leaning toward CGI now and stop motion is a little under sedge from CGI and so in some way stop-motion is seen as a very old fashioned medium these days. That’s the reason behind the set being renaissance themed with the illustration of Leonardo Da Vinci woven into the fabric, De Vinci also use to cut up cadaverous to see how they moved and I thought that was somewhat relevant to the animation as well. Also the man is dressed in Edwardian cloths because I wanted to reflect the idea that stop-motion is considered and old fashioned art form that also the reason why everything bras, bronzed and timber so it defiantly didn’t have a contemporary feel.

On top of that I took a gamble and shot the film on twos because I wanted it to be a little bit staccato and jerky so people would have absolutely no doubt it was being done by hand I was worried that people might of though it was just bad animation.

Going full circle Ray Harryhousen had the same problem when he was animating Talos the giant bronze statue in Jason and the Argonauts, he animated that without any ferrying on the moves, it clicks into place rather than gently moving into position that’s because it a giant robot thing, and the criticism he got when it came out “is Harryhousen loosing his touch” but he had done it intentionally!

So I tried to do the same thing with slight of hand this is clearly done by hand even down to the clay element on set I make sure to leave my figure prints in there. It’s a treaty on stop-motion and where it is in the world at the moment but also making a comment on destiny and free will, and weather that is an illusion.

I had just finished reading a book by Sam Harris called the ‘illusion of free will’ and I though some of the things he brought up were interesting, nothing to do with the film but the idea that people think that they are in control when really they are effected by so many environmental factors that are in are DNA that we cant fully shake of so if were given a decision if you know the genes that are in body we are more likely to get a predictable decision based on that than free will, it could be are body is already telling us what direction we should be going in even though we think were making that decision.

Your films do very well in festivals, and specifically well in Australia with ‘(R)evolution’ winning the Australian Independent Film Award and ‘Gargoyle’ winning Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Award. The Australian animation industry has a long-standing reputation, especially in stop-motion can you give us your opinion on how the Australian animation industry works and is looking at the moment?

I don’t know exactly why that is, its probably because we have quite a large immigrant population here, people from Easton Europe coming over helps a lot, as stop motion is vary big over there. My good friend Barry Purves said to me whilst I was in Stuttgart that its not just because you’re an Australian, but some of the strongest stop-motion in the world at the moment is coming out of Australia at the moment with people like Adam Elliot, Norman Yeend and Darren Burgess. I do think we have a very good reputation as stop-motion animators and I’m not really sure why that is I do sometime think it because of the isolation, we find it very hard to be effected by trends in animation that are happening in the rest of the world because its so difficult for us to get to film festivals for a start, you od get to see a lot of stuff online, but actually being there at a film festival is probably one of the most important things you can do as an animator, which is why I’m making the trip to Bristol, to try and get as much as a sense of belonging as I can because when you work in Australia you very rarely get over seas animators coming over.

Were a very small group and we all know each other and what the other persons up to, its sort of incestuous from that point of view. To go out into the wide world and mix with animators you’ve never met is very stimulating for a group of animators that normally don’t get to meet those sort of artist. But I think not being influence very heavily by other animators generally is a good thing as it means we can be quite intuitive.

Baring that in mind what are you planning for the future/what are you working on at the moment?

I’ve just written my next short film script that with my producer at the moment, it’s a very personal story as I’m very much of the persuasion that you should write about what you know, I wont give the plot away, its stop-motion again, its personal and very different form anything ells I’ve made. I believe having the abilities to make short films is a hug privilege that I’m acutely aware that other people have great story’s that they never have the opportunity to tell, being in the position I’m in I relies its very good position so I think it’s my duty as well as my pleasure to tell the story I want to tell.

We’ve also shot a pilot for children TV series, once again it’s a privilege position for us to be in, instead of going to market with a script we can go with an actual episode because we can make the set and the character and shoot it. So we hope that will give us an edge. Were also working on a couple of commercials, which will fund the new short.

You can see Sleight of Hand at this years Encounters Festival in the Ani 1: Power to the Puppets category (18th September, 10am).