Aardman’s “Lip Synch” 30th Anniversary Interview (Part 1)

In the 1980s, as the fledgling Channel 4 committed to investing in adult-oriented animation, one studio was particularly well placed to benefit. Aardman had already demonstrated a flair for “serious” animation with two shorts for the BBC, Down and Out (1977) and Confessions of a Foyer Girl (1978), in which expressive clay puppets acted out candid recordings of members of the public. This novel approach impressed Channel 4’s top brass, who commissioned five more films in a similar vein: Conversation Pieces (1983).

Wallace and Gromit and global superstardom were still some years away, but Conversation Pieces helped establish Aardman as a force in British animation and led to a stream of advertising work. By the time Channel 4 ordered another batch of shorts, the studio had grown in size and ambition. The title of the new series, Lip Synch (1989), suggested more of the same, yet the films themselves demonstrated an urge to experiment. Three of them — War Story and Going Equipped, by the studio’s co-founder Peter Lord, and Nick Park’s Creature Comforts — were indeed based on conversations with ordinary people; but these were structured as interviews, with strikingly different results. The other two, Barry Purves’s Next and Richard ‘Golly’ Starzak’s Ident, pushed the notional theme of ‘language’ even further, almost entirely eliminating dialogue.

When Lip Synch marked its 25th anniversary in 2014, we published an interview that focused on the Oscar-winning Creature Comforts. For its 30th we’re looking back at the other four segments, which are lesser known but brilliant in their own right. We headed to Aardman’s Bristol studio for a rare chat with Peter, Barry, Golly and Aardman co-founder David Sproxton (who was closely involved in producing and shooting the series). What follows is part one of a transcript that has been edited for length and clarity ahead of the full interview’s inclusion in an upcoming Skwigly Animation Podcast — check it out if you want to learn more about the relative merits of film and digital, the charm of coughing in animation, and fond memories of Donny Osmond in purple corduroy pants.

Paint a picture of what Aardman was like when you were making Lip Synch.

David Sproxton: It was a Victorian garage, basically. A 2,000-square-foot shed, which we rented.

Barry Purves: We were back to back. If you stepped back quickly, you’d bump into the next film. We used 35mm cameras, which took up a lot of space. We had video assist, but it was black and white, and not a true picture.

How did you come to be at Aardman, Barry?

Barry: These kind chaps gave me a job in 1986, after I’d been on [Cosgrove Hall’s] Wind in the Willows for six years. The same stories kept coming around, and I thought I had integrity, [so I left]. My first job for Aardman was the singing bra [in a commercial for Ariston]. I thought, ‘There goes my integrity!’

David: Channel 4 had started, which meant twice the airtime for commercials. There was this massive cash injection into the commercials market. They wanted stuff that was different. We happened to be there at the right time. We did an awful lot of commercial work in quite a short period of time, which helped build the company.

Richard ‘Golly’ Starzak: We had a fax machine. Advertising agencies would send through their scripts, and it came to the point where we ignored them till the end of the day. There was a pile of them.

You were employee number one, Golly. How did you end up at the company?

Golly: I’d done quite a lot of animation at college, in a surreal vein. Some of them were funny as well, but they didn’t go down too well at art college. It was like, ‘Art isn’t meant to be funny.’ I was shooting a little film in Bristol, and Pete and Dave came to see the sets, then they gave me some work. I didn’t think of it as a job — just as something nice to do for a couple of years.

Let’s talk about the Lip Synch films themselves.

Peter Lord: War Story and Going Equipped were both in a tradition we’d been working in for quite a long time: working with found soundtracks, rather than written ones.

But for Lip Synch you switched from candid, ‘eavesdropped’ recordings to interviews. Was that a practical or an artistic decision?

David: We’d realised that the ad-hoc nature of random recordings doesn’t work very well. You record a lot of stuff you never get to use. We’re not documentary makers, and we didn’t particularly have the art of getting to where the action was. So we thought, ‘Who’s good at doing interviews?’ We made contact with a number of radio journalists. War Story came out of a conversation with Peter Lawrence at BBC Bristol, who’d done a radio series on Bristol in the Blitz. He said, ‘You’ve got to meet this guy, Bill Perry.’ [Peter] did the interview for us, and Bill was this lovely character who you turned on and out came all these anecdotes. We recorded for an hour and a half.

Peter: Maybe more.

David: The other guy we found was Derek Robinson, who was both a drama writer and a journalist. Drawing stories out of people is quite a specialist skill. He did four or five interviews for us with various people: a bookie, a female climber, which we didn’t use. [Derek] said, ‘I know this lad who’s 21 and just out of prison.’ Because we’d done Down and Out and On Probation, we thought we’d follow in that vein. Derek recorded this guy, which became a monologue, and actually almost a confession. A bright young lad who’d just been born on the wrong side of the tracks. So we did a kind of classic middle-class thing of trying to get inside his head. All we had was what he was saying, and we tried to interpret the sort of life he would have had. The full interview was really fascinating — we could only use five minutes of it. So that approach — using good radio journalists — really paid off, and when it came to doing [the Creature Comforts series in 2003], we used the same approach.

Peter: The funny thing about War Story is that Peter Lawrence went to interview Bill Perry, and came back with a couple of hours of hilarious stuff. But unfortunately there was a technical fault with it, so it was unusable. But he just went back and did it again! These were Bill Perry’s oft-told stories — he was an old man by then. He was a great and very willing raconteur.

To what extent do these two films succeed on their own terms?

David: They’re very different. War Story is played for laughs. Going Equipped was very honest. I think we got a letter from a sociologist saying, ‘This is the most responsible programme I’d seen on TV for many years.’ Simply because it was a first-person testimony about, ‘Don’t do what I’ve done.’

Golly: I don’t know if I’ve told you this, Peter, but on the local news I heard a voice, an old guy, and it was the Going Equipped guy! He was being interviewed because one of his sons had, I think, got stabbed in a drugs raid.

David: I contacted Derek a few years ago, wondering what had happened to that guy. Derek had lost contact with him. I don’t think we’d ever known his name.

Peter: I’m pleased with the film. To make an animated film that didn’t try to make you smile at all seemed audacious at the time. For us, it was unusual to try to make something compelling without the crutch of humour. I must say, people never seem to like the film very much. [With War Story,] having got the recording, I toyed with making that quite a serious film as well. He’d clearly been quite traumatised by the bombings, and that post-traumatic stress disorder was part of his story. But we had Going Equipped already, so I was alright…

Barry: I always remember the film’s melancholy atmosphere. The lighting, with the water running down…

Peter: It was quite influenced by Blade Runner, where they’re sitting in the car, and the rain’s running down the faces… With Going Equipped, I was influenced by Yuri Norstein’s The Overcoat, which is unfinished. But it’s an incredibly beautiful thing: just an observation of this guy living out his small existence, without any gags, really.

Barry: Those films were so influential. So many people copied you without understanding exactly what you did.

Peter: It wasn’t our idea in the first place. We picked it up [from John and Faith Hubley’s films, for instance].

You didn’t meet your subjects before animating. Did you know look at photos of them?

Peter: No.

Did they see the films?

Peter: Bill Perry came to the premiere. He was quite a fan. We’ve stayed in touch with his daughter ever since.

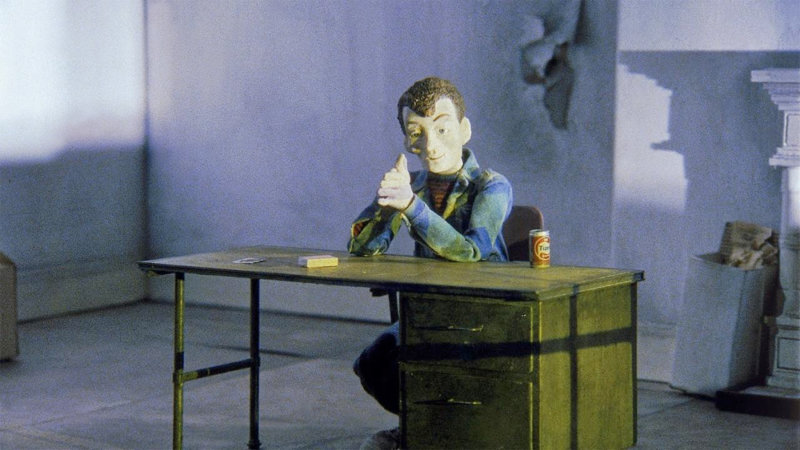

Golly, tell me about Ident. Does it still work today?

Golly: It was my first attempt at a professional film, which meant I didn’t really know a great deal about storytelling. I worked with a writer called Bill Stair, who wrote the TV series Boon. The design of the film is based on an American artist called Saul Steinberg — I really liked his work. The idea was to combine surrealism and comedy. I remember this quote, many years ago: if you take surrealism, in Europe it became quite dark and weird, but in America it turned into Warner Bros.

Which were you closer to?

Golly: I was split, I think. When I was a kid, you got one cartoon a week [on TV], after the football on a Sunday. They’d have a Road Runner or Tom and Jerry. And then I’d spend the evening with my friends, and we’d [dissect] it, redo the sound effects and stuff. It seems ridiculous, now that everything’s available to everyone, all the time. But then it was literally five minutes a week. So if they put on the same one as they did last week, I’d be furious! Which they often did, as it was just filler.

Always American cartoons?

Golly: I think so. I didn’t know much about British animation at the time. That came into daylight for me around the time Channel 4 started, and I was already working for Aardman by then.

So Ident was an attempt to synthesise these influences?

Golly: I think so. I remember telling myself, ‘Don’t put all your ideas in — just focus on one.’ But in the end, it felt like I’d thrown in everything and the kitchen sink. I look back on it and think it could have been four different films.

There’s a piece in the middle [of Ident] where two guys meet and talk in ‘man-language’. I wanted to do the whole film in this nice, rhythmic, almost poetic gibberish. I tried to do that with the comedian Arthur Smith, who was one of the voices, but I realised it would take months to get a soundtrack.

Barry, what’s your take on Next?

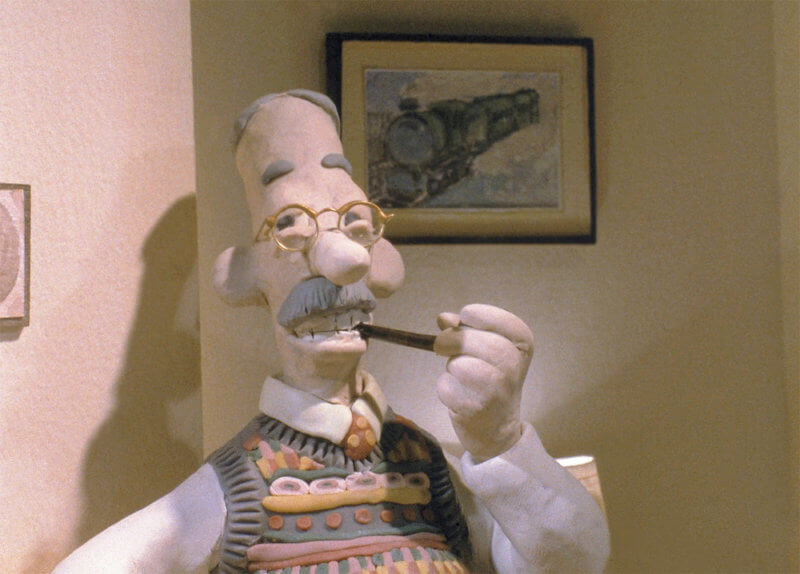

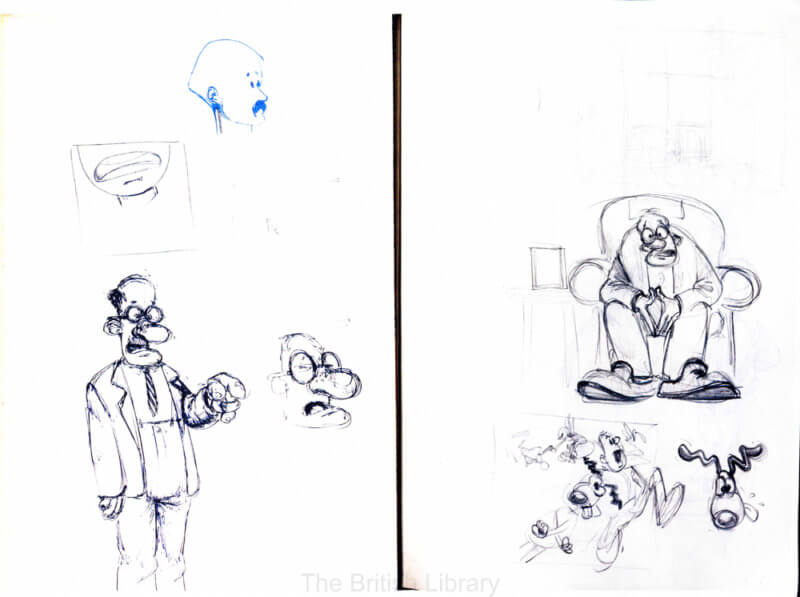

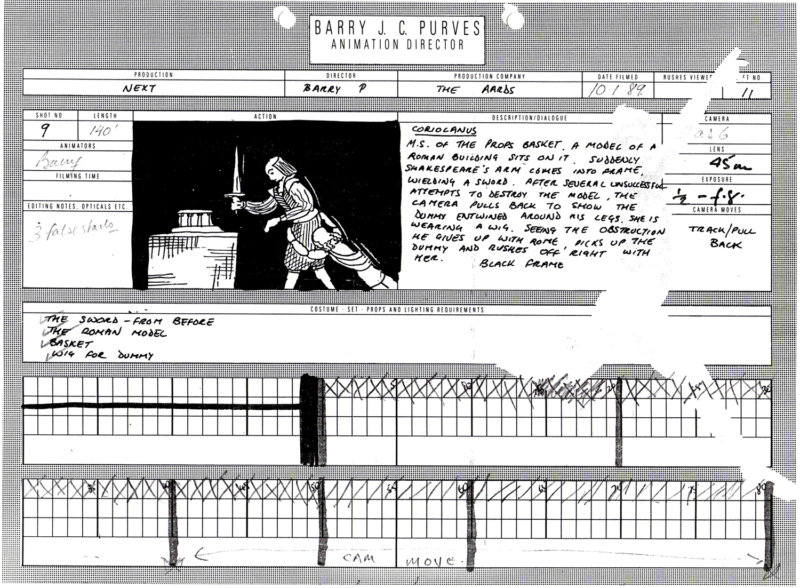

Barry: There was a brief moment where I thought to go out into the streets of Bristol and ask people about Shakespeare. And then someone told me that in Huckleberry Finn, the boys meet a travelling actor who does a cod-Shakespeare [performance] in which he does every play. I read it, and it was actually only two plays. But I had the idea of doing the complete works of Shakespeare in five minutes. In my mind, it was going to be all-singing, all-dancing; but the budget, which wasn’t small by any means, allowed me one major puppet. I thought, ‘I’ll rethink it — let’s make it about one puppet performing Shakespeare.’

Who made the puppet?

Barry: We can say now that it was Peter Saunders [of Mackinnon & Saunders]. He was working at Cosgrove Hall at the time, and wasn’t meant to do work on the side, [so he’s uncredited]. The puppet could still be animated now. It was beautiful — that’s where the budget went. And the clock at the end, that sunburst thing — this is a cheap bit of trivia — was found in a skip on the day I was filming! We were just discussing what the brief for the five films was, and I think it was to play with different forms of language. [I went with] body language.

A puppet of Peter Hall, the founder of the Royal Shakespeare Company, appears in the film. Did he see it?

Barry: I do believe we asked him to do the voice! I think he’d been made a sir that week, and he said, ‘I’m too busy now.’ But he did write a very lovely letter. The reason it’s Peter Hall, and I thank my mum for this, is: I first saw Peter Hall’s production — my mum took me — and it was so clear, so exciting. So the film is sort of a nod, a ‘thank you’. And also, he was a film director. He didn’t make great films… He made one called Akenfield, about life in a Suffolk village, which I was in! I was an extra in his film, so he’s an extra in mine.

Golly: Weren’t you snogging a girl in it?

Barry: Yes, I was! Oh, those days… Is it wrong to be obsessed with Shakespeare still? I’m still obsessed with him.

For more on Aardman check out our Skwigly archives and find the studio online at aardman.com