Akira: 35 Years of Influence and Inspiration for Anime and Beyond

It’s been 35 years since Akira first premiered at the Japanese box office on the 16th of July in 1988 and since then, it has become one of the most recognisable and iconic animated films in the world. Often cited as being one of the best anime productions of all time, even if people have never seen the film, they would have undoubtedly heard of it.

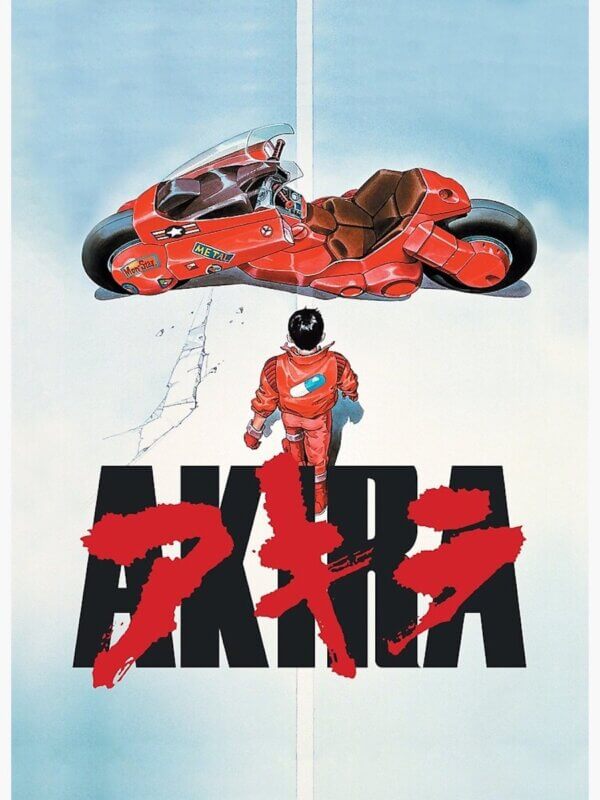

A dystopian future unlike any other, the film tells the story of a group of young rebellious bikers led by Shotaro Kaneda as their rivalry with other biker gangs eventually leads Shotaro’s best friend, Tetsuo Shima, to gain powerful psychic powers. But as Tetsuo slowly loses control over his god-like abilities, his friends are dragged into a threat that could see Neo-Tokyo destroyed as it did during the third world war.

The influence this film has on the animation industry, as well as other forms of media, is more far-reaching and impactful than some may not be as aware of. Whether it’s the animation techniques that make the quality stand out among modern animated films, taking advantage of video rental stores outside of Japan or its inspiration for future filmmakers and artists, it’s simply a piece of cyberpunk art that was able to stand out from the crowd of both live-action and animated titles respectively that hasn’t hit quite the same chord since.

And this all wouldn’t have been possible for a young manga artist whose love for cinema would eventually lead him to a directorial debut that the world has not seen before and, arguably, since. His name? Katshuhiro Otomo.

Katshuhiro was born in 1954 and raised in Tome, Japan. One of his biggest passions as a child was to go to the cinema, although he would have had to travel for three hours by train to get to Sendai in order to watch the latest films. His other passion was mangas and one of the most notable ones that inspired him in his work was Tetsujin 28 by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, a popular manga-turned-anime in the late 1950s and 1960s that featured imaginative adventures surrounding a boy and his giant robot. Despite the long journey to the cinema, his love for both art forms would become influential in his work as both an artist and a storyteller which would be reflected in his earlier work.

Moving to Tokyo to become a manga artist, he made short stories for the Weekly Manga Action publication before he attempted to create his own series. His first attempt, Fireball, may not have been completed, but he was able to demonstrate his more realistic drawings compared to other manga titles on shelves at the time. This didn’t stop Otomo from crafting his own stories and he would pursue his goal while also continuing to explore his detailed and gritty style.

Published in Action Deluxe Magazine between 1980 to 1981, Katshuhiro’s second attempt, Domu, captured the imagination of its readers as his dark and violent story saw a child and an elderly man with paranormal powers come into conflict as a series of mysterious murders occur within the tower block they live in. Domu became such a big success that not also did it win a Japan Cartoonist Association Award in 1981, but was the first manga to win the Nihon Science Fiction Taisho award as well in 1983 when it was published in volumes.

A Panel from Domu (© Dark Horse Comics. Source: Retrofuturista)

The success of the paranormal manga gave Otomo a platform to create an ambitious cyberpunk manga, one that was inspired by his childhood passions and use his approach to more adult-oriented stories to try and create something new and fresh in the industry. Weekly Young Magazine was willing to publish his then-latest story, which would famously become Akira. Starting out its publication in 1982, it became popular among the magazine’s readers during its 8-year serialization with its mature storytelling, gritty world, and unique character designs, Otomo also became a recognisable name in the manga industry in Japan and was given a unique opportunity to transform his panels into animated scenes when approached to adapt Akira into an animated feature.

While this may have been a daunting task for some manga artists to jump in the director’s chair, Otomo actually had some experience while exploring other creative projects when he gained popularity in Japan. Between 1982 to 1987, he directed some short films as well as being responsible for creating segments for the feature films Neo Tokyo and Robot Carnival. This gave him the experience needed to adapt his own manga and test himself by working on a full feature-length production rather than smaller pieces of animation.

TMS Entertainment was founded in 1946 and before picking up the rights to produce the pages of Akira, they were responsible for a number of successful films and television shows, including the Lupin the Third films, New Tetsujin-28, and Sherlock Hound. As impressive as some of the previous work from the animators at the studio was, Akira would see them being pushed with access to bigger resources than ever before as Japan enjoyed a successful economic boom that the studio would take advantage of with an estimated 700 million yen budget.

With 70 people working alongside him, Otomo and TMS Entertainment were able to use full animation and animate across 24 frames of the film, which not many studios did as they more often tried to cut corners or animated fewer frames to save time and money. Using full animation creates detailed movements and higher quality with each second animated into the production and was only achievable by all those involved with the production and making use of the large budget to do so.

Akira was released in Japanese cinemas in the summer of 1988 and had a good result at the box office, earning 750 million yen that year. It would take over two years until the anime would finally be at UK cinemas on the 25th of January in 1991, although you had to find one that was willing to play it compared to the more family-friendly Disney films that audiences were more used to. While the film continued to perform in its home country, Western audiences would re-discover this across the 1990s with an emerging and popular market.

Video cassettes were on the rise and being able to buy your own tapes and rewatch your favourite films and television shows without having to wait for them to appear on a television channel opened up a new revenue for studios and distributors to explore. And with video rental shops like Blockbuster ruling the home video market, it created and popularised a new part of the media industry before it evolved into the modern video streaming service that everyone is familiar with today.

While many were happy to pop in Hollywood hits from that decade like The Lion King, Jurassic Park, and Titanic into their VCRs, the home video market was also a great opportunity for anime to establish itself and saw some titles become cult classics. Among them was Akira, which would become more readily available compared to the brief broadcasts it had on BBC Two. Despite the limitations on the number of titles available for those to rent from Blockbuster’s shelves, this would be enough to spark an interest in anime. This would lead to the emergence of hit anime television shows like Dragon Ball Z, Pokémon, and Sailor Moon making their way to the small screen, which in turn would eventually see a treasure trove of shows and films available for a global audience for a whole new generation to enjoy.

With different ways to be accessed across the globe, many people discovered Akira and since its premiere all those years ago, its impact on animation, storytelling, and cinema as a whole can’t be underestimated nor undermined.

With the large economic boost that Japan had in the 1980s, studios looked at the success that Akira garnered and wanted to adapt existing manga or create new stories in the animation medium that would explore cyberpunk and futuristic sci-fi tales. Some of these titles like Cyber City OEDO 808, Battle Angel Alita, Appleseed, Bubblegum Crisis, and Ghost in the Shell were able to make use of their large budgets to try and tell mature stories while also showing off the skills of the animators involved.

Hollywood saw a surge in more mature sci-fi stories and dystopian future settings that challenged the political and cultural landscape throughout the 1990s as filmmakers were most likely influenced by the mature animated films and shows coming from Japan. Films like The Matrix, The Fifth Element, Event Horizon, 12 Monkeys, and Terminator 2 helped to make sci-fi much more engaging and thought-provoking for adults, challenging the norms of science fiction that they would have grown up with as children and introducing something like they have never seen before. And this would have a ripple effect on the growing video game industry as well as the large-budget productions of modern television shows, with Stranger Things, Half-Life, Foundation, and Cyberpunk 2077 all continuing to build upon what they learnt from watching the filmmakers and writers who were inspired by anime and films at the time.

One of the reasons Akira is so fondly remembered today is the recognisable and iconic imagery, whether it’s the cycle skid, Tetsuo’s horrific mutation, or the details in the colours and layers of the explosions and effects. Television shows such as Batman: The Animated Series, Steven Universe, Rick and Morty, South Park, and Big City Greens have either directly referenced or parodied these scenes entirely, paying respect and homage to something considered a masterpiece in animation. Even as recently as this year can the film’s influence be felt in animation as Puss in Boots: The Last Wish had some inspiration from Akira for the explosions and effects as it features so much style and colour in its designs that the director of the film used these scenes to inspire some of the effects in the Dreamworks production.

But what about Katsuhiro Otomo? How did his famed creation inspire and influence his career after his masterpiece’s release across cinemas and the home entertainment market?

While he did write a few more manga series, they, unfortunately, didn’t quite hit the same level of success as Domu or Akira. However, Otomo was interested in his career as a filmmaker. After pouring his heart into the creation of cyberpunk fantasy, it’s not hard to see why he would want to try and top himself after its success and the groundbreaking efforts of the animators he worked with. While he penned the scripts for the sci-fi animes Roujin Z and Metropolis, he would eventually find himself in the director’s chair for Steamboy, a steampunk anime that had plenty of visual spectacles on offer with its 2.4 billion yen budget (the most expensive anime back in 2004.)

As for his future, Otomo is currently working on his 3rd anime film named Orbital Era. Telling the story of a group of young men in the near future, who find their lives tested while working on the construction of a space colony. While it may not be close to release anytime soon, it looks as though this could potentially be something that would be worth the wait.

Whether it’s your first time watching it or your hundredth, this film deserves to be watched and celebrated for its major milestone as it has inspired and influenced so many filmmakers, artists, and writers. It’s truly an anime masterpiece that deserves to be explored and with 35 years of history in the art of filmmaking and animation, what better way could fans and newcomers could mark the occasion than by finally picking up the remote and press play on this unique sci-fi tale?