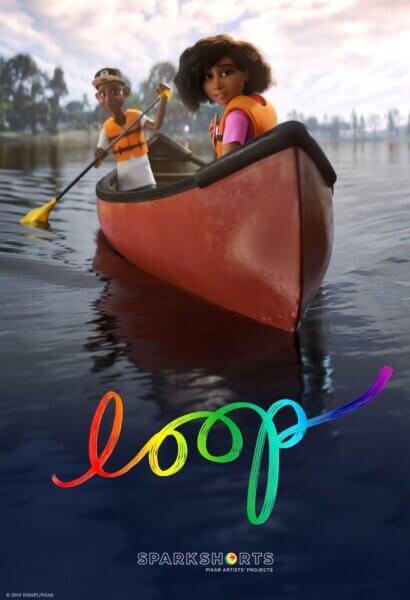

Autism Awareness Month: Pixar’s Loop – Interview with Erica Milsom

April is a very important time of year for many autistic individuals and their families as it is also known as Autism Awareness Month. We are celebrating and raising awareness with a series of interviews with producers, writers and directors who have created animated content around this subject.

As both a writer for Skwigly and a proud autistic person myself, I want to thank everyone involved who has made it possible to share these amazing behind the scenes stories and what they have learned on productions that have become important to them. Here I speak with Erica Milsom, director of the Pixar SparkShorts film Loop; a short about a chatty boy and a non-verbal autistic girl, learning to understand each other.

How did you start your career at Pixar and how did you get involved with the SparkShorts program?

I started my career doing Finding Nemo years and years ago and they hired me in as an assistant editor, part time, for three months. It’s been about fifteen or sixteen years. It’s been a long time since then (laugh). But I was hired in because I had experience doing large scale documentary projects and on Finding Nemo, Andrew Stanton really wanted to make an actual documentary about how the films come together. So I was there to sort through footage, log, transcribe. I think I cut a few little things. But basically I fell in love with the place and the crew who were creating these documentaries.

For the first couple of years I was laid off during the in-betweens because in the olden days, the films didn’t come out every year so in those days it took a lot longer for the films to come out. We didn’t make them right on top of each other in the same way. I went and did other things, but I would always come back to work with these crews on these amazing movies. Some years after that, I think it was on the Cars Blu-ray, I ended up moving from assistant editor to director and co-director with my friend Tony who was the DP at the time, we congealed and made up the documentary department. So I’ve been doing that. I’ve been doing behind the scenes documentaries and other documentaries for museums and stuff and covering Pixar’s every move for fifteen years (laugh).

I’m trying to remember the year when the SparksShorts had been a thing and they made a few SparkShorts and I was like “Wow! I love this program.” I had actually taken advantage of another program at Pixar called The Co-op – a program where you can work with collaborators at the studio in your off hours using studio equipment and resources. It was an amazing way to engage with filmmaking to explore things outside of your job to work with folks across the studio who maybe you wouldn’t meet otherwise.

So I made two films through that, a documentary called Snow Day which was an hour long documentary about a group of senior citizen skiers and a live action fictional short film called So Much Yellow and from those two I realised I loved working with the Pixar team. They’re amazing. They’re dedicated and excited filmmakers and they love working on fast side projects. We all love making the feature films, those films are amazing, but having a sort of chance to play in a field that’s a little less needing to be a blockbuster (laughs), it gives you a chance to play with some new ideas.

I had done those other things and I finally just went up and talked to Jim Morris the president and I was like “Hey . . . president.” I know Jim (Laugh). It was kinda one of those weird moments where I was like “I have this idea and I know that you are a fan of my films of the past and have been such a great supporter.” Jim’s an amazing ally for me and so I was like “This is the idea and I would like to do a short about two kids trying to connect, one of whom communicates with an electronic device.” And he was like “Oh that sounds interesting. Let’s see about it.” So that was how I got into the SparkShorts project. I think the reason why I was selected was that I’ve done so much work in the past in collaboration with other people on the side, they were like “Oh, ok. Let’s see what she can do.”

With Loop featuring Pixar’s first non-verbal autistic character, what was the journey like to write the story and create Renee?

That’s a great question. I had been inspired to tell this story by some time I spent volunteering at an arts centre for adults with disabilities and some of those adults were folks who did not use words to express themselves and they connected in different ways. It was always kind of awkward for me in the beginning because I use a lot of words to express myself (laugh). I’m a very chatty person. I use a lot of words and I found that in this environment my efforts to connect were always using a lot of words. If I felt awkward I would use more words rather than less and that didn’t work (laugh). It didn’t get me closer to folks and I needed to find a different way. That was sort of the impetus for it.

I didn’t know Renee was autistic when I first started thinking about this story. I knew she didn’t use words to communicate and I knew that she would use a device to help her communicate, but I honestly didn’t know much about that character so I started asking people questions. “Why do some people not talk?” “What are the causes for having a non-verbal relationship to communication?” And as I went around and asked these different questions, people told me about autism and started to explain that autism had a communication component and also had this sensory component.

The process of writing Renee was what I feel was the ideal creative process where you start writing down what happens and then you start asking yourself “How does this person respond?” And then you start asking yourself why? Why does this person respond in this way? It quickly dawned on me that I had to listen to as much information as I could. At the time it wasn’t a formal project so I couldn’t get formal advisors so I basically went to YouTube and listened to autistic people talk about their stories as much as possible. Just observing as much as I could about their experience and their expression of themselves and what they had to say about their life and their character and the way they react in situations and I started writing that into the script. But I do feel like it was always driven by a character having a journey in mind and then stopping and being like “I don’t know what she would do right now that would be different. I should go ask.” Which is basically listening to people talk about their experience.

When the project became a formal project at Pixar, I ended up bringing on advisors from the Autistic Self Advocacy Network and also one of my friends, who is autistic, they came in and read the script and watched the early story reels and gave us advice. As we had questions and as they had questions, we would talk about what their responses would be in these situations and what things that might feel honest or what don’t really feel true to someone who is autistic or non-speaking experience. So their help was a huge part of finding authentic responses for Renee.

Erica Milsom is photographed on November 13, 2018 at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, California (Credit: Photo by Deborah Coleman / Pixar)

What did you learn from collaborating with the Autistic Self Advocacy Network?

First of all, I learned some basic ideas about autism. I learned that autism is a neurological difference and that it has a very broad spectrum. I learned that it had a lot to do with communication, which I hadn’t really understood. So the way that people process and use words who are autistic can vary really, really greatly. There are some folks who can use lots and lots of words and like to really talk through an experience and connect through speaking and there are people who don’t use words at all and have a hard time accessing spoken language when they’re trying to express themselves. So that was one thing and that was definitely that Renee was going to be one of those folks who had a hard time accessing spoken language.

Each autistic person is different as much as any neurotypical person. But sometimes they have a different sensory experience in the world so they can have this amplified experience of sound or of light. Their brains take in a lot a lot of sensory information and it can be overwhelming sometimes to process that for them. So that was definitely exciting cinematically. It felt like being able to be inside the point of view of a character who was processing the world differently than a neurotypical person might be a really exciting creative opportunity.

They informed me about stimming and stimming is this process of using your body. A lot of people have this, like sometimes if you shake your knee when you’re nervous or you tap yourself. There are things that people do when they are trying to sooth themselves and for some autistic people, stimming is part of their experience and it’s when they move their body physically in a response to things. We really wanted to put that in Renee’s gesture vocabulary and work with animators to express that. It was just so fun for them to work in that body language. That vocabulary was very different than they had done before.

The last thing was that basically they let us know how rare it was to see a female character on film who was autistic and even more rare to see a person of colour who was autistic. Those kind of limits, in the way that the media portrays autistic people, are reflected in doctors’ likelihood to diagnose people of colour as autistic and I just thought “Wow. I want to have an impact on that. I want to shift that dynamic if we can.”

What was it like to direct the animators and represent autistic people on-screen?

That was amazing, I have to say. Number one, Pixar’s animators are pretty world class. They’re pretty wonderful, talented people and the other thing about them is that they’re very curious and they’re interested in human behaviour. They’re interested in the interpretation of emotion.

There would be these quiet sessions where I wrote down notes for every single shot because I knew that we needed to work quickly and they needed to have as much information about it for every single shot that they encountered. So to understand what Renee was feeling, to understand what might be some of her gestural responses was really important. The thing that I loved about the animators is that they all sat there and they all listened together and the listening is so deep. The director’s talking and everybody’s listening, but being the director in that room it’s like “Wow, is it ok if I am talking this much?” And the animators will be like “Yes! Keep talking!” They were just soaking in anything. They were seeking a performance that works over the arc of the film with these two characters whose identities they don’t necessarily share and they just want to learn as much together about those characters and how those characters would react.

That was just amazing to be in this group of people who were so attuned and interested and we did an hour long presentation for everybody who came on about autism and provided tons of reference. I think for all of our animators, they never really had a close relationship with anyone who was autistic so learning that gestural vocabulary and learning that different way of responding emotionally was new to them.

It’s a SparkShort so it’s got a smaller budget and very, very quick timeline so I would run around in walkthroughs and see people’s work in progress. Myself and Ali Sadegiani, our amazing animation supervisor, would work through any problems they had and test it and be like “Ok, does this feel right? Does it not feel right? What are some of the solutions we can come up with?” Overall, that group of people just blew my mind. They were so tuned in, so dedicated, so curious and they’re so talented, right? (Laugh) They did something that so exceeded my hopes.

The autistic community has overall really, really embraced it as a representation of “Yeah that feels like my experience.” For many people they said that. It’s kind of phenomenal. That’s the first time I’ve seen that expression of experience on-screen in a character who’s fictional.

Still from Loop (Credit: Pixar)

The one thing that we did, for example with Renee’s stimming, in order for our animators to understand a gestural language to express her emotions, was we broke her emotional responses down into five categories. If she’s happy, she flaps her hands. She does a bit of rocking if she’s upset. She rocks the boat physically if she wants to say no. But basically that was a huge win for the animators to sort of say that here’s the behaviour she would most likely represent in this situation so if we know the emotion of the moment we could also map this kind of gestural response to that emotion.

So that was helpful for everybody because you are learning another language and it’s not like learning Italian. I love this about non-speaking people. They have this intimate language with their family members and their friends that’s very much based on a shared expression of vocabulary and people learn how to read each other’s gestures and stimming to understand the emotional map that happens to that physical language. We needed to do that with our animators. It was a really cool process.

What was it like to direct Madison (Bandy), who not also was the voice actress for Renee, but is on the spectrum herself?

It was really fun. I really liked Madison. In the beginning I went to audition her and I awkwardly sat next to her while she made her art and I just listened to her. She knew I was there and she knew I was there to listen to her voice, but she is a little bit guarded with new people and is more likely to lose access to language and vocalise more when she’s feeling uncomfortable. So it was good for me because I learned a lot of what her voice was sitting next to her because sadly I made her uncomfortable, I think. Not terribly, but when you’re sitting next to someone and you’re like “I don’t really know what to say.” I feel like that’s what was happening between us.

We interacted three more times before the recording session. I think she came to Pixar twice and each time we got more and more connected and close and recognised each other. By the time we got to the recording session it was like… we are very connected. Some things we needed to direct like getting her to sing the ringtone – we needed to get the right voicing of that. Some stuff we wanted to hang out and capture what her actual vocalisations are. It’s not things that she pulls out on command, but they are there if you spend some time with her. It was amazing! It was so fun! She came to Pixar, but she felt very overwhelmed when she was at Pixar. It’s just very stimulating.

After she came to Pixar we were like “You know, I don’t think it’s the right place for the recording.” So we ended up taking our engineer Vince Caro with us to her house and did the recording there and it was super fun. It was like half documentary, I’d say, where we just hung out and captured her vocalisations; and it was half directed, when we needed things that she had to say and we sent those ahead of time so her family could practice with her. It wasn’t hard at all. It’s funny, I guess. I’ve worked with a lot of people with disabilities and a lot of people with intellectual disabilities so I don’t find it particularly challenging to figure out how to direct them.

To me, directing actors is about freeing up performance. It’s about finding a way together to get to the thing you’re hoping to get. So with Madison, sometimes I would push her hands if I needed her to make loud noises or be upset. In order for her to respond like someone had thrown her phone away we pretended like we gave her a shot in the arm with just your finger and she would go “Aaah!” And singing the ringtone, she did that. She’s very musical, her whole family is very musical so the ringtone singing was very easy for her. We set up the right situation for her and then treated it like any recording session where it’s partially improv, partially directed, but trying to get to the most playful and emotional delivery possible.

I’ll be honest. I really loved Loop because I’m on the spectrum myself and –

That’s awesome, Martyn! Thanks for telling me!

Still from Loop (Credit: Pixar)

For me, I really liked the film and the relationship between Renee and Marcus, because it reminded me of my time at school and how different children with different disabilities would communicate with one another and try and have a friendship or relationship. I was curious what the reception for the film was like since it was released on Disney+ from different groups or families; or even autistic people?

Well that’s so interesting because that was my most terrifying thing – “would autistic people like it or feel represented well or would they feel like it’s making fun of them?” I would say 99% of the people that I have heard from have been so delighted by it and really felt excited. I heard a lot from people who are autistic and speaking and they have really, really loved it and felt connected to Renee in a way that I was like “Yay! That’s so cool to hear that!” The last thing I wanted to do was make a film that made people feel made fun of. Part of the power of having it on Disney+ is that it can have a broad reach, so I wanted it to have a strong, positive reach.

And then families definitely reached out. I think about ten people who are non-speaking reached out to me since then; whether through the internet, where we have internet chats, or some folks made appointments to have a Zoom meeting where they do assisted conversations using a touch board to tell me how they responded to the film.

Actually, somebody wrote to me the other day who was really mad and didn’t like it, which I can understand. Sometimes we don’t like movies, but I was like “Tell me why” and then we had this amazing conversation and by the end he said “I’m really glad you made it.” It was just so funny. I think it’s hard. I’m sure you had this at school. If you communicate different, if you have a different way of interacting with people, I think there’s a lot of emotional baggage to that, right? That’s a really interesting part about being a filmmaker – that you evoke feelings and I always hope to have the conversation with the audience because I want to learn from people’s experiences.

It’s been pretty amazing. I feel so grateful to have all these amazing autistic people who reached out who became the process of making this film, but who’ve reached out since to share their impressions and their thoughts because I went from this person who didn’t know anything about autism to this person who is always going to try and be a better ally by learning as much as I can. And also, I’m amazed! You guys are interesting people!

I hope that as people learn and as neurotypical people become more aware of autism and their differences it sparks a curiosity and respect for the way that your experience of the world might be something that we as neurotypical people can learn from. That’s how I felt about Renee. She taught Marcus something through the process there. She helped him to see this lake that they both travel on as a different place with different opportunities; different dangers. They had a shared experience.