British Animation in WWI – Frightfulness v Fair-play

To accompany “Frightfulness v Fair-play” a talk at the BFI Southbank on the with a programme of British Animation from WWI and live musical accompaniment, Jez Stewart of the BFI takes a look back in time at the origins of the British animation industry.

Name a British animated film made before, let’s say 1940. Got one? If you have, pat yourself on the back, but then name me another one. Now I’ve got you. Knowledge of British animation in its first 40 years is pretty sparse, perhaps even for avid Skwigly fans. Len Lye’s A Colour Box (1935) is the one that people are generally aware of – it has been well described on this site by Stephen Cavalier for his 100 Greatest Animated Shorts series, and is a touchstone of animation history internationally. But the careers of the men (seemingly exclusively into the mid-30s, I’m afraid) who laid the foundations of the industry in the UK are sadly forgotten. At a pinch you might get the name Anson Dyer out of the extra keen, but what about Dudley Buxton, Lancelot Speed, Joe Noble, Victor Hicks and others?

One good reason for their obscurity is the lack of access to their films. They’ve been available for viewing by keen researchers – usually on 35mm film prints – on the premises of archives for many years, but have not been in easy reach. Thankfully this is changing. Archive digitisation schemes such as the BFI’s own Unlocking Film Heritage (UFH) programme is putting more and more archive footage online, of good quality and wherever possible for free.

Whilst you will have to wait until spring 2017 for a dedicated animation collection in UFH, animated films have cropped up in other themed programmes from the project thanks to the wonderfully diverse, Swiss army knife properties of the medium. For example, see the programme on “Public and Information Films” for some newly digitised versions of the cult classic Charley Says series which have really brought back the colours and details of Richard Taylor’s original cut-out work.

And if we look back to, not quite the b of beginning, but the start of a national animation industry in the UK, there are already quite a few films available that can start to flesh out the history. When Edwin Starr argued that war (Huh!) was good for absolutely nothing, he had obviously not considered its impact on British animated filmmaking. For example, take a look at John Bull’s Animated Sketchbook No. 4 from June 1915.

What we have here is a mix of different traditions: the lightning sketch (a live drawing performance popular on the music hall stage); the political/editorial cartoon developed in newspapers and pamphlets from Hogarth onwards; the nascent comic strip; postcard humour and aesthetics; and the still relatively new medium of the cinema. We could perhaps even add to that proto-VFX in the recreation of the sinking of the Lusitania. OK, so it is not a patch on Winsor McCay’s 1918 film The Sinking of the Lusitania but one was released three years after the incident and one after six weeks.

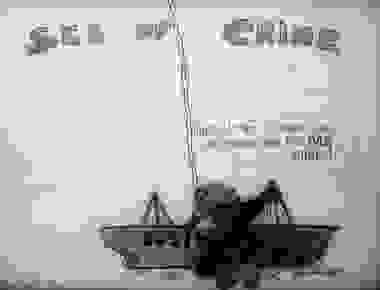

Studdy’s War Cartoon: A Sea of Crime (1915)

The opening sequence with “Bill” (aka Kaiser Wilhelm II) and the lyre/liar gag is pretty good – it is a short, sharp, comic piece of propaganda with a gruesome end that would be horrific in live action but you can imagine raising cheers in cartoon form. It’s a visual joke that packs the punch and immediacy of a good editorial cartoon, but the joke could not work in a static one-panel without a confusion of sequential drawings. Animation brings it to life.

The hand that appears throughout the film belongs to Dudley Buxton, aged 31 at this time and working on what was at least his 7th or 8th film. He spent the decade before the war working as a comic “black and white artist” for weekly illustrated tabloids like The Tatler and illustrating postcards which were experiencing something of a Golden Age. Despite his 20 years in animation Buxton is better known for his postcards which can easily be found online or at collector’s fairs. It’s noticeable that he wore a suit jacket and shirt, presumably with a tie whilst at the rostrum – when did the last animator go to work in a tie?

Some of the scenes need contextual references to fully appreciate. Alfred Von Tirpitz was the Großadmiral of the German Imperial Navy, and therefore the figurehead of blame for the torpedoing of the British civilian liner the RMS Lusitania by U-Boat 20 on the 7th May 1915 and the loss of 1,198 lives. The incident had enormous propaganda value for the Allies – particularly as the 28 US citizens killed had the potential to rouse America out of its neutral status. Morphing Tirpitz and the Iron Cross into a skull on the Jolly Roger pirate flag is another powerful, politicised image, and again one which requires animation to be fully effective.

The “Motoring” scene is an appropriation from a popular music hall sketch by performer Harry Tate (hence the apologies) in which he played a chauffeur trying to start a car to drive his idiot son to naval college. Dudley Buxton casts Kaiser Wilhelm II in the Harry Tate role, complete with the comic’s trademark twitching moustache, and his heir apparent Crown Prince Wilhelm naturally fits the son role.

The representation of Chaplin resonates more easily over the years, but the reference to “The Fly Peril” on the newspaper he holds is a now very obscure reference to marketing campaign for a product called “San-Fly”. Throughout the summer of 1915 a column entitled “National Crusade against The Fly Peril” appeared in a variety of newspapers, looking much like a news story but almost certainly a paid advertisement. To follow up you could apply to the “Secretary of the Anti-Fly League” League sending one shilling tuppence per packet – “post free”. Although Chaplin’s character is familiar, the image of him with a frothy pint of beer is much less so. Chaplin was excellent at playing the comic drunk, but as he took more control of his films and built “The Little Tramp” it is something he distanced the character from in favour of a more childlike innocence and mischief. It seems a little odd to see him in a British pub, but don’t forget Chaplin had only recently crossed the pond from his South London roots, and the Tramp character did not debut onscreen until February 1914.

And suddenly I am over 600 words into an analysis of a film that it is easy to dismiss as obsolete. I would argue that this somewhat archaeological exercise is of more than parochial interest. What we have here is animation being used to directly engage with the cultural, political and social environment that surrounds it. It is a film that was made to be relevant to a wide audience and was shown in cinemas as part of a mainstream film programme. That is not a situation that is easy to recreate today, and in fact was challenged even within the duration of WWI as American animations produced with more industrial methods came to dominate screen time. But I would hope it is certainly of interest.

The parts of these films that do tend to drag today are the lightning sketch sequences. Dudley Buxton’s choice in this film to show the steady uncovering of his scenes by filming him blacking his drawings out and then projecting this in reverse is an unfortunate one. Observing the actual skill of an artist at work has more interest, but the balance between sketching and animation steadily turned in preference of the latter. These scenes were useful for the filmmaker as they could be produced faster than true animation and there was a pressure to turn the films around quickly to remain topical and stay affordable.

Another reason to pay attention to these early works is that the growth in sophistication in animation was exponential whilst it was supported by the patriotic production bubble of the war. As proof I leave you with a later Dudley Buxton film released just two and half years after the previous example. The artist’s hand makes only a fleeting guest appearance to a film which demonstrates how much Buxton had learnt about characterisation and narrative in that short time. What starts as a comic tale of the man on the moon heads into a far darker science fiction territory.

A programme of British Animation from WWI “Frightfulness v Fair-play” with an introduction by Toby Haggith of the Imperial War Museum and Jez Stewart of the BFI will be screened at the BFI Southbank on Tuesday 25th July 2016 at 18:20. To find more animated films on the BFI Player look at the ANIMATION & ARTISTS MOVING IMAGE genre page.