Interview with ‘I, Barnabé’ director Jean-François Lévesque

I, Barnabé, the newest film by the talented animator and director Jean-François Lévesque, expertly combines multiple forms of animation including intricately designed puppets, 2D animated stain glass windows, traditional watercolour animation and mesmeric fluid sequences.

The film follows a priest as he learns to acknowledge and ultimately accept his darker sides in order to strive for a better, more enlightened self. The complexity and intricate detail on display in the film is a masterful achievement for both Jean-François and his team. Produced by Julie Roy at the National Film Board of Canada, the film should be recognised not only for its performance and storytelling, but its multiple technical achievements and advancements in new areas of production.

In anticipation of the film’s inclusion at this year’s Annecy Festival, Skwigly were very lucky to get some time with Jean-François to discuss some of the technical – and emotional – research that took place in order to create the film.

How did you first become involved with animation?

I chose to pursue a career in animation because it was the logical continuation of things I had cared about intensely as a child. At four years old, I already had a passion for making little three-dimensional paper figures. Later on, I became interested in drawing, painting, and magic tricks.

After high school I studied fine arts, then took courses in traditional 2D animation. Animation allowed me to combine all the passions of my childhood in a single profession. When I graduated I immediately started work in animation. I’ve been involved in every aspect of the industry for 20 years now.

Your work in the past has often combined mixed approaches to animation. What is it about this way of working that interests you/drives you forward and do you ever encounter technical complications because of this approach?

Very early in my career I decided not to specialize in any particular branch of animation. That choice runs counter to current thinking, which emphasizes super-specialization. I like the idea of being able to pass constantly from one technique to another; it keeps me involved and interested.

So when I was given the opportunity to make my own films, I naturally wanted to incorporate a lot of different techniques, and at that point I realized that every technique has its own poetry. That’s why I use different technical approaches in I, Barnabé, to suggest the character’s experience of different states of being. The fact that I wanted to mix different animation techniques in the same film did complicate my life enormously, especially in terms of the investment of time that was necessary, because the stages of research, design, and experimentation had to be repeated with each new approach.

The puppets make use of intricate and often complicated clockwork head systems, what are the advantages for you of this style of facial animation over something such as replacement mouths and/or faces?

The technique of face replacement using 3D printing seems to have become standard in stop-motion animation. I can understand why big film productions like that approach, because it allows them to break up the work, giving separate tasks to different people and pre-animating a character’s facial movements virtually with 3D software. Plus, with this technique they can be sure the character stays “on model” even when the work is being done by two animators whose style may be quite different.

For this project I chose to use mechanical heads because, as a working context, it’s more fun and creatively much more stimulating. With a puppet like Barnabé, what you have is a real little actor who can do everything, with no extra bits that have to be added or taken away. It’s easier to feel free, to improvise and let yourself go. And because there were only two animators working on the project, it was possible for us to take this approach.

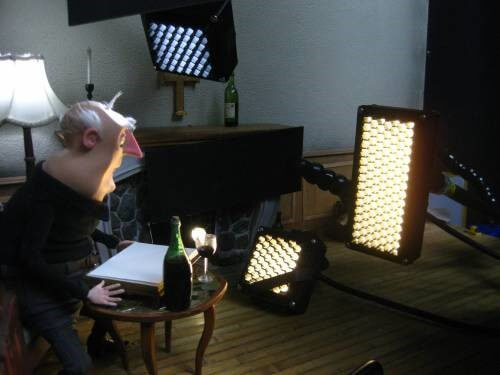

Light sources as installed during filming (image courtesy of the NFB)

I was very impressed by the miniature-scaled LED panel lights created by the production team, they almost give the illusion of the puppet being life-size. What do you feel these production details of the multiple passes and scaled lighting give to the final film?

We made the decision to build our own miniature LED panels because at the time nothing of the kind was available commercially. Our idea was to create a kind of lighting design that would be different from the traditional way of lighting puppets. If you think about it, lighting a miniature world from one metre away with a 300-watt Arri is the equivalent of lighting a human actor from 10 metres away with an enormous floodlight. Our idea was that by using miniature light sources we could get closer to the subject, and at the same time we would be better able to control the effects of illumination on the puppet.

When it came to multiple lighting passes, the idea was simply to be able to modify the ambient light, that is, to adjust the light sources or shut them down completely once the animation was finished. I like to think that these technical choices give the film an original and subtle look. But they also complicated our lives hugely by making everything that much more difficult.

I, Barnabé is a truly striking film, everything from the sets and puppets to lighting, special effects and script really showcases your experience and maturity as a filmmaker, did the film turn out as you wanted?

Thank you for these kind words. I can only say that the final result is quite close to what I hoped for. I didn’t have to make too many compromises. For that I have to thank my producer, because we did encounter setbacks at various stages of the work, and several times we had to go back and start all over again, particularly in post-production.

The film deals with a classic struggle between the two aspects of Barnabé’s ego, both in himself and as part of the church he works within. Can you tell me a little about what inspired the story and what personal connection you have with the themes in the film?

That’s it exactly, you’ve got the central theme of the film. The character of the rooster, for me, is an externalization of the priest’s ego, a materialization of the struggle playing out in his mind. At the outset, Barnabé refuses to see or recognize the darker elements of his being, but as the story unfolds, he becomes aware that he has to accept those aspects of himself so that the task of inner integration can begin.

First he has to deconstruct himself, letting go of his attachments to his identity, his social status, his past, his beliefs. It’s a kind of stripping away of all those things. The inspiration for the film is the archetypal journey that most of us have to make at some point in our lives when we’re confronted with adversity.

The film feels partially self-reflective, as well as a statement on the church, about the duality and often hypocrisy at work within organised religion and faith, it can be a very uncomfortable subject matter to discuss but also crucial, why did you want to tackle this yourself?

I do want to speak out about these issues, and to explain why I felt compelled to do that, I should mention that I grew up in a small Quebec village in the 1980s. At that time the Catholic religion was still omnipresent in our lives, and in my family especially.

Being a skeptical child who questioned everything, I had a lot of trouble accepting religious dogmas. I wanted to challenge every one of them. It made me angry that the people giving us instruction about these beautiful concepts so rarely lived up to them themselves.

As an adolescent I completely shut myself off from that part of my upbringing, as so many adolescents do. Nearing adulthood I became completely materialist. I lived in complete spiritual emptiness.

When later on in my adult life I was confronted with death and the absence of meaning, I was forced to reopen the door to the fundamental questions. But this time I chose to make the journey alone, conducting my own spiritual search and my own experiments, not following any path laid down in advance or inscribed in any religious doctrine.

I think that today it would be possible to speak of the spiritual aspects of life, if we could agree to let go of certain dogmas that we tend to cling to at all costs. We also have to accept that dogmas can be found everywhere, that they exist in science and atheism just as much as in religion.

You mentioned in a previous interview that you’re aiming for perfection in your film, in order for the audience to forget about the film being animated and believe instead that the characters are truly alive in order to achieve greater emotional realness. In that regard what advantages does animation bring to the filmmaking and storytelling process?

First of all, I make absolutely no claim to have achieved perfection. The very concept of perfection is relative and illusory. What I can tell you is that my striving for a kind of perfection in animation is linked to my childhood love of magic. Perhaps, like me, you let yourself be seduced by magic when you were a child. If at that moment of enchantment you had seen the magician slip the card into his sleeve, the spell would have been broken. You would have felt let down, because you so much wanted to believe it was true.

Looking at it that way, you could say that animation is an elaborate hoax, a deception based on an illusion of movement created artificially in the viewer’s brain.

And so, for me, what is the reward for all that time spent creating an animated character? Probably the moment when the magic succeeds and my illusion convinces even me. Although, of course, that doesn’t always happen.

With that in mind, do you have any interest in creating a live-action films?

When I watch live-action films, I have great difficulty making the “leap of faith” that would let me forget that it’s all staged, not real. That may seem like a strange response, but cinema in general seems false to me. So I prefer to work in the medium that is the ultimate in artificiality—animation, of course.

The film is just starting its film run, have you managed to get any feedback on the film so far?

The only reactions I’ve had so far are from the media. They’ve been quite positive. People seem to get the point much better than I ever imagined they would.

The ongoing pandemic has seen a lot of events, including Annecy, shift to online editions. From a participating filmmaker’s perspective, how have you found this transition?

At first it just seemed to me that I had chosen to launch my film at the worst possible moment. For a while I was hopeful that the festivals would still take place as usual, just at a later date. But when I finally realized that the lockdown wasn’t going to end any time soon, I began to see that the festivals, Annecy and the others, were right when they decided to make their programming available online. It’s a good decision.

What are you working on next?

For the moment I’m still taking on animation-related contracts, but at the same time I’m feeding the reflection machine to develop ideas for my next film.

Annecy Online festivalgoers can catch I, Barnabé in the competition screening Official 2 until June 30th.