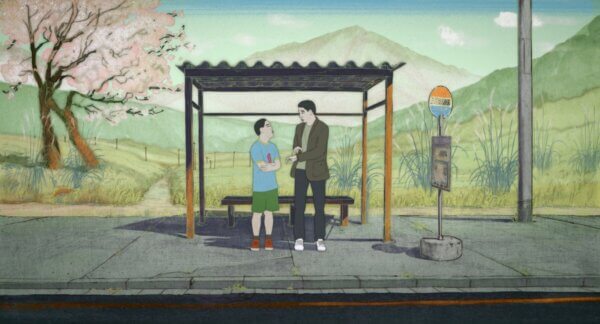

Pierre Földes on ‘Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman’, an Animated Adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s Short Stories

There is little difference between an earthquake and a divorce. Both sweep away load-bearing pillars of a town or of a mind. Everything you take as a given when you wake up one morning is lying in pieces in front of you by the end of the day, all that’s left for you to do is pick them up and try to figure out a way to keep going.

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman is a collision of these two ideas of disaster. Some disasters are communal, perhaps national, much like the earthquake and tsunami which underscores every scene in this film set in 2011 Japan. But disaster can be personal, too. It may not leave an imprint on the earth itself, but for one person it is an apocalyptic event.

Pierre Földes’ adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s short stories follows characters trying to make sense of disaster. Whether they’re an ageing, balding, lonely banker who daydreams about being recruited by an off-puttingly anthropomorphic frog asking him to save Japan, or a middle aged divorcee, living life on auto-pilot, trying to find a cure for his emptiness. Abstract, quiet and reflective, the film is a character study of people looking for meaning.

In this sense, the film is a departure from the source material. Murakami’s stories are segregated, often being pulled from different books to forge the narrative Földes looked to tell. The director himself has had a rather scenic career. Having grown up wanting to be a painter, Földes shifted into music composition before finding his way to making films. Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman marks his feature directorial debut.

Wanting to innovate from the start, Földes implemented an experimental cousin of rotoscoping for this film. The entire film was shot in live action, but instead of being traced into animation, the footage was used as a reference for animators to study the subtleties of human facial expressions and mannerisms.

Földes talked to Skwigly about the look of the film, finding his way to animation and the mechanics of adapting Murakami’s work. Here is that conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

How have you gauged the reaction to the film?

The reception has been really fantastic. One thing that makes me very happy is that the reception from the younger generation, late teenagers until about 28, they seem to really get the film and embrace it and understand it in the way it’s supposed to be understood. That means they just take it all in, and it inspires them in some way. They’re not too analytical, trying to make sense of everything. The film actually does make sense, it’s just not that easy to understand. But they accept it like that, maybe, because they’re used to seeing all kinds of confusing images, and they just take it all in.

Your journey is quite interesting, from being a visual artist, to a composer, to now a director. Was this the plan?

It was planned, but sort of a delayed plan. My father was an artist, painter, and animator. And so for me, it was obvious that I wanted to be an artist. I was always drawing and then something weird happened. I just switched and went into music for some odd reason, and I was quite good at it. And so, I just went into classical training for composition and orchestration and I sort of let go of the visual arts, but never completely. I started working as a composer, I was moving between New York and Paris, then I moved again and I went to Hungary where I went back into painting, suddenly. That was fantastic because, at that point, I thought, “Wow, this is unquestionably what I should have done all my life.” So I had some kind of regret, I must say. I just love it. I love oil painting, I love the smell of it. I love the brushes, I am really passionate about it. It’s amazing.

I also started making films and when I was very young, I acted in theatre and did some stage direction. I’m a little all over the place. The odd thing is that I started making short films really late [in life]. I just found myself suddenly going back into drawing and really finding interest in pencil drawing. Then little by little I got into animation, but developed my own technique. I had no training in animation which was really wonderful. It made me much more eager to create stuff, to create a style, and to always look for something new.

Do you think having not a firm basis in animation helped you innovate on the animation style we see in Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman?

Completely. I get lots of questions from students and young animators and artists [about animation] but it’s not like I have massive experience. But I would be almost tempted to say the only thing that’s interesting is finding your way. This depends on, are you trying to be an animator working for this or that studio? Or are you trying to be a musician working here and there? Or is your aim to be an artist? I mean an artist, somebody who is doing something absolutely unique, that nobody [can do] by recreating something. I’m only interested in that, but I totally understand that many people can be interested in being the best Disney Style animator or great jazz pianist. It’s fine, it’s just not my thing.

I found it really interesting that some characters and some objects were drawn with white outlines instead of black outlines, as would be traditional. What was the thinking behind that?

So, there’s many ways to answer. The first one would be to say that it’s just my stylistic approach, my style that I’ve developed for this film. To go a little bit more in detail, I could say that it’s an interpretation of my perception of things. So as opposed to, let’s say, photography, live action, where you take a camera, and you print what the lens is seeing. You’re getting a 2D image that’s more or less realistic. When I think of the way I see things, my brain is working all the time which is affecting the way I perceive things. My aim, when I’m making a film, is trying to reproduce my vision. So the way this works is, I have a character who’s focusing on this other character, but then there’s something in the background which is not very important, and so it’s [shown to be] blurry. Or maybe I’m not paying attention to that person, but I still know that it’s this shape, and this far away. It’s a sort of enhanced reality, but totally subjective.

Reality is a really important aspect of the film because there’s so much shifting between dreams and reality. What were the challenges of depicting those transitions?

I remember really paying attention to that even when I was beginning to write the script. I’m writing the script, and then I’m doing the storyboards and I’m thinking, “How am I going to be able to shift here and there?” I wanted to avoid these moments where [the audience] thinks, “This is real and now I’m in a dream.” In order to do that, my approach was to always keep reality a little bit off, and always keep the “dreams”, somewhat connected with reality. That way, it makes it smoother, and you’re not going from one to another, it’s always there.

What were the most difficult visuals to pull off in the film?

If something is difficult, I don’t see it as difficult. I see it as something I don’t know how I’m going to do, and this is exactly what I’m interested in. I’m only interested in diving into a world that I’m attracted to, without being able to define it. If I can define things beforehand, then it’s just a job and I know how to do it. Everybody can do it. What’s interesting is if you feel that there’s something attractive here, some emotion or some relationship, you dive in and you think, “How am I going to find my way out? How am I going to transcribe this?”

Did you have the idea to tie Murakami’s short stories into one large narrative from the start?

No, to be honest, it wasn’t from the start. In the beginning, it was going to be segmented, there was going to be four or five stories. Then little by little, I started thinking that this character could actually exist in this other story. And when you start mixing them up, things get tangled and you have to find solutions. This was my solution and it made sense. In the end, it made a sort of full circle, because when I put everything together, I needed to separate it again, that’s why I created chapters. It was nice for me to give a little separation, a little breathing room in between, like you’d normally put a book down at the end of a chapter.

How much of yourself did you want to put into the film versus respecting the source?

I don’t know. I mean, I had no plan, it just happened. Let’s say you’re an actor, you’re playing a written part, but at the same time, you’re the one who’s doing it, you are the one incarnating that character. So you read these lines by Murakami, of course, it’s his words, but at the same time, the way these words impact you, that’s you, that’s yours, it’s not Murakami anymore. If these words touch you, they touch you because of what you are, because of your life, because of your knowledge, your experience, who you are. So then, if you decide to use this to express something the way you feel it, it’s yours. It’s completely inspired by you.

The stories you pull from are set in such a specific time in Japanese history. Did you have any apprehension about tackling this real life event?

I just love those stories and I thought there was some humour in it also. I was never trying to be faithful to anything, I didn’t try to recreate a real Tokyo or real Japan, it was my vision of it. I’m always pointing out the fact that I’m just an artist, I’m not trying to be authentic, it’s fiction.

What was the biggest lesson you learned from making this film?

Don’t do animation. Forget it, it hurts. You have to be truly of masochistic nature to go into making a feature animation.

Are you a masochist?

I guess so! But I’m cured. Not anymore. I mean, it’s wonderful, it was just a bit too long… well, much too long. I thought it would take me two years from beginning to end, but it took so much longer. It’s completely crazy to make a film at all is nuts. Now I have many more projects. One is live action with a little animation, then I have another one that’s full animation. But I’ll cross my fingers, I hope I’m going to manage to pull it off a bit faster.

Do you think he could have pulled this film off in live action?

Yeah, I think so. I have no idea how I could have done it, but it’s possible. The Frog would have been an issue, but not really, he might have not not been a frog, it could have been just a weird character.

Have you made your dream film, composition or work of art?

I am only interested in making stuff, so there’s no such thing. I mean, I’m super happy to be making films, [this] was just far too long. In the world of the film industry, the problem is it’s an industry. Finding funding for a film and then releasing it, there’s all that work around it. I’m only interested in making stuff! If somebody wants to hire me tomorrow to direct actors, I’m there. I’m interested in the creative path. That’s it. And if I could go from one creative activity to another one, I’d be happy.