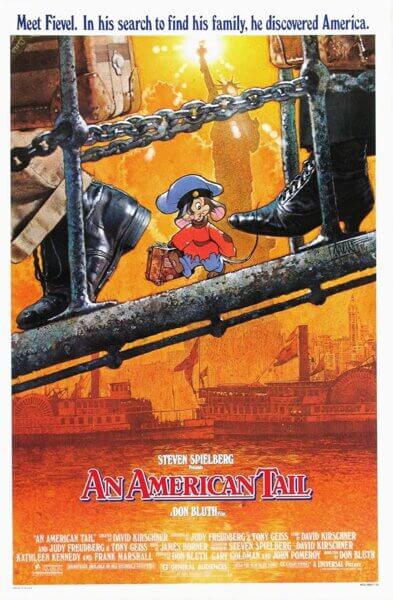

“There are no cats in America and the streets are made of cheese” – An American Tail Celebrates 35 Years

Thirty five years ago this month, audiences would be introduced to Fievel Mousekewitz, a mouse who escapes the dangers of cats from Russia with his family to the promised land of America. It’s historical setting and its portrayal of immigration both educated and entertained children and with its themes of family and unity, it’s no surprise that it is still watched and praised today.

The film should be celebrated for many reasons: it’s relevance on immigration in America today; how the artistry from the animators still remains strong in animation; and its relevance in shows and films that celebrate pop culture. But, for me, it’s the fascinating history behind the film’s production and how the talented filmmakers got involved to create a film that tried to tell an important story. So let’s step onto this opportunity and look at what made An American Tail one of the most important animated titles to be released in the eighties.

Don Bluth started his career as an animator at Walt Disney Animation Studios, being part of the team that worked on Robin Hood (1973), Pete’s Dragon (1977) and The Rescuers (1977). After spending many years there, Bluth was ready to move on and direct his own projects and he left the studio in 1979, which resulted in seventeen other animators joining him. This one action would have repercussions on the film being made within Disney at the time, The Fox and the Hound (1981), and pushed its production back by eighteen months.

Now being on his own, and setting up Sullivan Bluth Studios, he directed his own team of animators on his first feature length film The Secret of NIMH (1982). Despite their efforts, the film didn’t hit as hard with audiences as it did with the critics at the time. However, it did catch the attention and inspired one famous director: Steven Spielberg.

After his work directing E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (1982), Spielberg was inspired to produce animation after watching The Secret of NIMH and approached Bluth with an idea of mice immigrating to America, which was based on the life stories that his grandfather told him about coming from Russia and into the US. Bluth and his team were onboard and ready to collaborate with Spielberg and his studio Amblin Entertainment. With Spielberg and his studio attached to the production, Bluth had a lot more support and collaboration with many new departments as well as his talented team of animators.

David Kirschner came onboard to help develop the story and joined the writing team. He was responsible for expanding Spielberg’s idea for what he wanted this animated film to be and expanded it, creating the adventurous Fievel and the Mousekewitz family.

But his original concept was only half an hour long and was set in an all-animal world in the same vein as Disney’s Robin Hood. Bluth was against this narrative approach, learning as an animator at Disney that those films weren’t successful then and instead should follow in the footsteps of The Rescuers where the animal world live in secret parallel to the human’s. This caught the attention of Spielberg and after a screening was arranged for him to see The Rescuers, he agreed with Bluth on his proposal to change the narrative focus.

Judy Fruedberg and Tony Geiss joined Kirschner after their work as writers on the successfully long running television series Sesame Street (1969 to Present). With this trio of writers, they were able to collaborate and bring their experiences together to tell a heartfelt story on immigration and family while also breaking down the hard truths of history and discrimination for children to understand and react to. It also helped to expand it into a feature length film instead of the thirty minute running time it started out as.

Throughout the production, Spielberg would learn a lot about the intricacies and effort that went into animation. He would check the storyboards that Bluth would draw up and he would write his feedback, which sometimes led to them both editing and adding scenes on the spot. Spielberg also wanted to cut some scenes that he deemed to be too intense for young children, which Bluth and his animators learned to cooperate on.

As well as being able to teach and show Spielberg the effort and process that goes into animation, Bluth was able to share his responsibilities with others. This included bringing on Lenny Leker as his assistant on the storyboards, guiding the writers on how to best approach a story that could rival what Disney was making at the time and give the characters his signature designs and appeal while also contributing to the requirements of Amblin’s marketing team for merchandise and publicity. And just as the production was starting to come to a close, the music would unexpectedly cause a new hurdle for Spielberg and Bluth.

Both Cynthia Well and Barry Mann wrote a number of hit singles for several musical talents including country singer Dolly Parton. James Horner was invited to join the talented duo to write the songs to be included in the film’s soundtrack.

But they certainly had a large obstacle ahead of them: they only had four weeks to write four songs and they were writing them at a much later timeframe within the production schedule then desired. Ultimately, this would result in some scenes being trimmed to feature the songs in the film.

But this tough decision would pay off as one of these songs, “Somewhere Out There”, peaked at number two in the charts at its initial release and also won a couple of Grammy awards. While it was also nominated for an Academy Award, it ultimately lost to “Take My Breath Away” from Top Gun.

Despite the challenges and obstacles, the film’s success in the box office and the enjoyment that Spielberg had producing an animated film to bring his idea to life, Bluth and Spielberg would work together for The Land Before Time and All Dogs Go to Heaven, both of which are fondly remembered by kids of the eighties. Even though they didn’t work on animation together again as of writing this, Spielberg’s enthusiasm for exploring and creating animated characters wouldn’t stop there. As well as producing nineties animated shows like Tiny Toons Adventures (1990) and Animaniacs (1993), he would adapt the iconic Tintin books and got into the director’s chair with his first animated feature The Adventures of Tintin: Secrets of the Unicorn (2011).

After his collaboration with Spielberg, Bluth continued to direct feature length animated films throughout the nineties. These included Thumbelina (1994) and Anastasia (1997), but with the introduction of computer animated films, he eventually moved away from working for cinematic releases after Titan A.E. (2000). While Bluth may not be back directing feature films for a new audience, he is helping to hone the skills for a new generation of animators. He set up an online course called Don Bluth University where he teaches students for one year about designing characters, storyboarding scenes and writing scripts.

Fievel and his family were not just the sole responsibility of these few highly talented individuals, but the large crew of animators and artists who were hired and worked under Don Bluth to bring Spielberg’s idea of immigration to life. Their success would help to make the film a success, with it being the highest grossing animated feature in the US at its initial release. Their efforts would also make An American Tail a franchise, spawning several sequels (both theatrically and on the home video market) and a television series throughout the eighties and nineties, all of which would help to give many animators their break into the animation industry. But above all, it united two great filmmakers to craft a story and bring life to a character who after thirty five years, we still celebrate and honour today.