100 Greatest Animated Shorts / Autobahn / Roger Mainwood

UK / 1979

Establishing their studio in London in 1940, married couple John Halas and Joy Batchelor went on to run what was for decades one of the largest and most successful animation companies in Europe. Underpinning their commercial and artistic success was their belief that animation was an art form that could be used for good and these humanitarian concerns inspired much of their work. Halas was a founder member of international society ASIFA (Association Internationale du Film d’Animation) which he saw as part of his philosophy of building bridges between animators of different nations, to work towards world peace.

In artistic terms they have been called the ‘British UPA’ although, due to Halas having trained in the Bauhaus philosophies, they were experimenting with modernist design before the establishment of the American company, who they were also friendly with. Due to the studio’s invention, creativity and resistance to turning their animation production into an industrial conveyor belt, they became one of the world’s most influential, long lasting and prolific animation companies, producing over 2,000 films in genres ranging from propaganda and information films to television series and feature films.

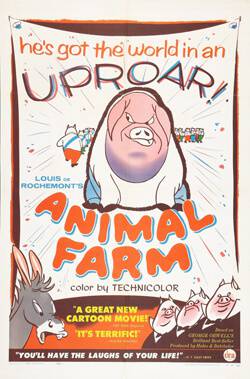

After starting out making commercials, encouragement from influential producer John Grierson led Halas and Batchelor (like many other animation studios worldwide during World War 2), to use the medium of animation for something it is ideally suited, the communication of ideas in an entertaining and accessible way. Many information and propaganda films were produced by the company as part of Britain’s war effort, while post war came more government sponsored shorts. Best know of these are the ones featuring the character ‘Charley’ to announce and popularise the introduction of those monumental achievements of British society, the social security and National Health systems. The studio followed this with many more examples of more sophisticated adult aimed work, such as their classic feature film and most famous work, Animal Farm (1954).

Joy Batchelor was one of the few female animators working in that era and all well as animator, writer and designer she was director of many of Halas and Batchelor’s films including other musical connections Ruddigore (1966) and the TV series Jackson Five (1971) and The Osmond Brothers (1972). This meant that the ever dapper John Halas knew he was leaving things in safe hands when he had to take care of business and go off to one of his many meetings. As a young animator I was interviewed by Halas late in his life in his house in Hampstead and was awed by the fact that not only had he made the time to interview me, a young nobody, for an important position which realistically I stood no chance of getting, but unlike myself he was immaculately turned out in a smart suit in his own house. Another story that was related to me by another animator who, on a visit to Halas and Batchelor’s West London studio, met John Halas coming down the stairs, traveling sideways, very slowly, taking one step at a time. When they inquired if he was okay and needed any help, he said he was fine, he just didn’t want to crease his suit trousers.

During the fifty-plus years of their studio’s existence, one of the reasons for their success and survival was constant experimentation with different techniques, a David Bowie-esque process of constant reinvention and openness to new developments, from low-tech paper cutouts through to being one of the early pioneers with computer animation (dating back to experiments in CGI in the late 1960s). This was guided by John’s background in the Bauhaus beliefs in embracing modernism and technology in art, which instilled him with an approach towards computer technology that led him to see it as an aid rather than a threat and which foresaw and welcomed the widespread use of CGI.

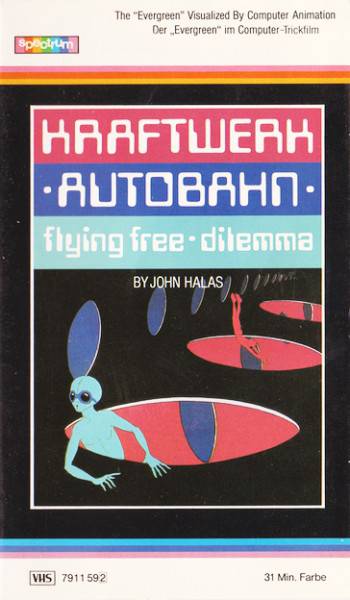

Just short of his company’s fiftieth anniversary, Halas hired Roger Mainwood, a young animator fresh out of college, to direct Autobahn, with the idea of setting the latest developments in computer animation against the revolutionary electronic pop of the new German group Kraftwork. This was typical of Halas’s encouragement of young talent as well as his spirit of experimentation with technology. After this early helping hand from Halas, Mainwood would go on to have a long and illustrious career as a director and animation director in film and TV.

Autobahn is essentially a music video for the Kraftwork song of the same name, produced late in the history of Halas and Batchelor studio, but named in a recent Sight and Sound magazine as perhaps their finest achievement. It’s one of those films, like Yellow Submarine, that is so perfectly of its time that it paradoxically has a sort of timeless quality and never seems dated, encapsulating the cold robot glamour of the band and evocative of the kind of optimistic trippy futurism that was one of the pop culture features of the era.

With the New Romantic movement gaining popularity in youth culture at this time, the electronic music and futurist styles of the video would have gone down a treat.

The use of the enormous analogue computer at the Imperial College proved to be less practical than hoped on the Autobahn project however, and the primitive images it produced were little used in the film, so in the end the film was animated by traditional methods. Nevertheless Halas saw the experiment as worthwhile and as good publicity.

This strange phenomenon of traditional cel animators being hired to fake CGI images, in order to give the impression of technological advances that didn’t in fact exist yet, wasn’t unique to Autobahn and was used on other ‘computer generated’ projects at the time such as Halas’s own Dilemma (1981) and the Disney feature Tron (1982). For traditional animators at this time it was in some ways something akin to digging your own grave while promoting your own death, as films such as this spread excitement about the possibilities of computer animation and increased acceptance and demand. Two decades after Tron, traditional animation would be pronounced in terminal decline with Dreamworks and Disney cancelling all future 2D animation in favour of the more profitable CGI productions.

This doesn’t mean that Halas’s optimism was misguided, as his was the big vision that saw animation as a whole and not just as the ‘traditional’ techniques. CG of course was the future of animation and in the years to come computers helped animation became more popular than ever, except now using genuine computer imagery, meaning the the jobs for traditional animators who didn’t adapt became more scarce.

Aside from its refuges in kids TV and commercials as it died a death in cinemas in the west, one more place that kept 2D animation alive during early part of the twenty first century was another genre also viewed with suspicion and dismissed as gimmicky by many western animators as it grew in popularity in the decades before. Anime hit the big time with Western audiences with Akira (1988) and caught the imagination of a new generation of animation fans with its demonstration that 2D animation didn’t have to look like Disney, consist of formulaic fairy tales or be aimed at kids to be popular.

In the cyclical nature of things traditional 2D animated features are starting to make a modest comeback (in Europe at least), new productions often aided by computers, telling grown up stories aimed at more arthouse adult audiences, and a major example one of these such film is Ethel and Ernest, currently being directed in London by none other than Roger Mainwood.

Note: The 100 greatest animated shorts is a list of opinions and not an order of value from best to worst. Click here to see all of the picks of the list so far. All suggestions, comments and outrage are welcome!