The Legacy of George Pal: Interview with Arnold Leibovit

After the launch of Arnold Leibovit’s second collection of Puppetoon shorts, Skwigly were able to get some time to discuss the legacy and workmanship of the late great master of puppets, George Pal.

The Puppetoon Movie Volume 2 brings together some of Pal’s best and most sought-after shorts, accrued from exploring dusty archives, backlots, storerooms, contacting the family of long lost collaborators and various European collectors and institutes, including the BFI. Through Arnold’s tenacity, many a lost gem has been saved and restored for current and future audiences alike.

Perhaps most commonly known for his influence in the live-action sci-fi genre, Pal’s fluid animations – made possible due to his innovative use of intricate replacement parts which has since become a widespread method – have directly inspired entire generations of top-tier filmmakers. His Puppetoons studio was a mecca for anyone and everyone wanting to engage with stop-motion animation, offering training to many young enthusiasts including the legendary Ray Harryhausen.

Prolific, industrious and kind in equal measure, Pal was his own worst promoter, often downplaying his accomplishments and putting other people’s achievements in his productions first. This humble nature is seemingly the reason for his often reduced credit among the early pioneers. Having a personal fondness and adoration for both the visual and narrative style of Pal’s animated works, it was a great pleasure to be able to learn more about this great man, not only from someone who met and knew him and his family but has gone to tremendous effort to catalogue and preserve both his work and the testimonials of those who worked with and loved the man himself.

Could we start by discussing your relationship with George Pal and how you came to work with his family to create the various productions about him and his work?

I grew up seeing Pal’s films, I was nine years old when I saw The Time Machine which was life changing for me. I think it was his sense of awe and boyhood wonder that really impressed me, the sense of heart that I found in his film which was so different to anything that had really been done at that point. George was really a prodigy.

Later on, when I was working on a science fiction film, I was friends with Dan O’Bannon (Alien) and he said I should meet George Pal. At the time I wasn’t following Pal’s career and I actually didn’t know he was still around.

So I was put in touch with George and I met with him at his house, which was a life-changing moment for me. Sitting in his living room seeing all the puppets and Academy Awards, I couldn’t believe I was sitting there talking to him. He was such a sweet man, he was very affable and self effacing, you couldn’t help but love him. So that’s how I met him. We stayed in touch for a better part of a year. Unfortunately, he passed away which hurt me. I was still in touch with Mrs. Pal and I told her that we really need to do something for George, some kind of tribute, as nothing had ever been done before.

Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit

Can you tell me a little about Pal’s origins and influence on the industry?

He became the head of UFA (a prominent German motion picture studio)’s animation department at twenty one years old, for several years. Then he – keeping one step ahead of Hitler who was investigating him as a foreign national – was the head of three animation studios for over twenty years, before he ever made a feature film. He was a producer, a director, an animator, a story designer, an artist. He was a real renaissance man. In Hungary where he grew up, he became an architect because he could draw. He used to say that in Hungary before you can be an architect, you either had to be a bricklayer or a carpenter. So he chose to be a carpenter because it was too cold for him in Hungary to be a bricklayer. He thought this was a really good idea, that if you’re going to become an architect, you should work from the ground up and know what it takes to be able to build. But he learned that he actually enjoyed being a carpenter. So that gives you an insight into his personality; he was hands on.

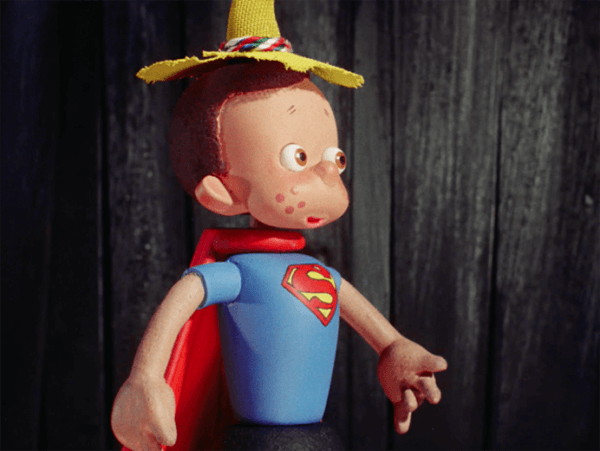

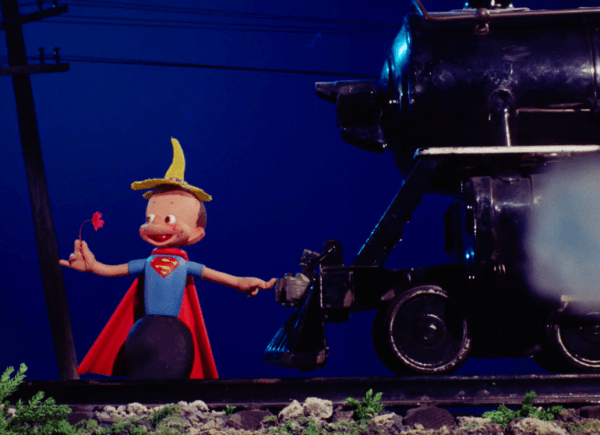

Good Night Rusty (1943 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

He was born into an actor’s family, his parents were travelling actors. So he had the Dramatic Arts in him, but he said he didn’t want to have anything to do with the stage. But the stage found him – he was a natural born showman. He moved from country to country and landed in Eindhoven where he set up an animation studio that Philips helped sponsor for him. It was the biggest dimensional cartoon studio in Europe. He made his ‘story films’, which were like commercials that we see on television today, but the commercial element became the smallest part of the film. There would be a three second part about the product within the rest of the narrative film but the audience loved them. So Philips said “do them”. They were such a hit that he was called the Walt Disney of Europe. He was very well known. So he’d already been the head of a studio in Germany and head of a studio in Holland for seven or eight years. Then Paramount became interested in him, so he came to the United States where he was very well known.

A Hatful of Dreams (1944 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

He and Walt Disney became friends. He influenced Walt Disney – when Disney was striving to have three dimensional animation with his triple plane animation stand, when he went from Mickey Mouse to Silly Symphonies to Snow White in 1930s, along came George’s Puppetoons – which had been starting to show up in the United States – and Walt was blown away by them. They were greatly influential on Disney, so much so that when George was making Puppetoons, animators came over to his studios and worked for George on them. One was Fred Moore, who is probably one of the great character animators at Disney. He developed the individual characters of the seven dwarves in Snow White. He also did the best, in my opinion, Mickey Mouse, in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Fred also worked at Georges studio, he made Punchy and Judy, from Together in the Weather.

A Hatful of Dreams (1944 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

There’s something so different about the films that stand them apart, so original and unique. There are very few great names of cinema and I think Pal is one of them. He’s not as recognised as he should be. The Academy did eventually recognise him, – he has a lecture named after him that was started by all the people that loved him. So every year or so, they have a famous person come and speak at the Academy. So the industry knows who George Pal is, it’s the world that doesn’t fully recognise his contributions to the motion picture industry. He was such a humble guy, he helped so many people get a leg up to become successful in the industry. And he never took credit for what he did. He would always defer credit to other people.

It must have been such a huge undertaking that was clearly sorely needed, why do you think it hadn’t been done before?

That is the mystery of the ages. I don’t know why no one had taken the effort or time at that point in history or even today. I also don’t know why George was overlooked in many ways. When I made the film about him I had no idea the epic nature of his involvement in the industry was worldwide. I kind of knew how the fans felt about his films, I just never knew the depth of it.

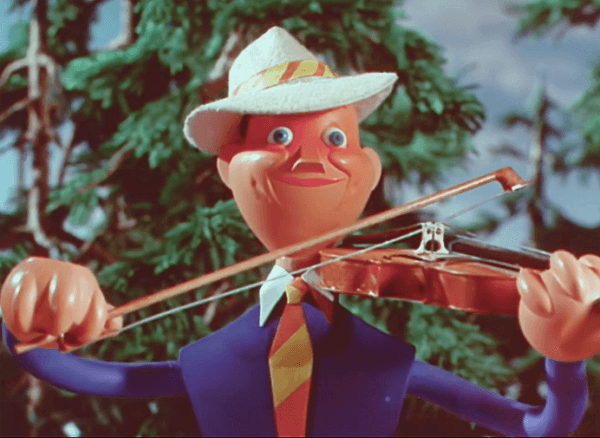

Dipsy Gypsy (1940 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

For the most recent collection you’ve mentioned you were able to find some new work in Europe, including here in the UK at the BFI, could you tell me about that?

I was thinking some of the films he might have made in England would make sense. And it turns out that some of them had been donated by different companies to the British Film Institute. They didn’t really know what they had. A film called Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves hadn’t been seen since 1935. It premiered in France and it was only seen a couple of times. That, to me, was one of the greatest finds at the British Film Institute. It’s really quite a remarkable film. I was able to restore it and it’s an extraordinary use of replacement figure puppets, the likes of which I’ve never seen before. It’s gorgeous. He has dozens of galloping horses in the desert. Each horse is a series of stretches and moves; it’s a spectacle of puppets.

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1935 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

So yes, that was a major discovery. I don’t want to give too much away but I’m working on volume three and, as we speak, there are discoveries that are being made now, for films that have not been seen ever, that are buried in archives in England, in Czechoslovakia, in Germany and in Hungary, some of which I will include in the next volume. Film archaeology is really amazing. I’ve tapped into something I never dreamed I would encounter, that these things would be alive after a hundred years, nearly, which might not have been seen since they were originally screened.

What were the challenges in the creation of the new collection?

Firstly, there’s no money in it. I’m doing it for the love of George and because I feel compelled to do it. I’m driven to do it but the challenges have to do with finance, getting the money and getting the support to do it. The rights aren’t a real issue. I was after the Paramount Puppetoons, which is a staggering collection of films in terms of quality and the fact that the successive negatives even exist, because cartoons were relegated to the dustbin by the industry. There were various companies that had some films besides Paramount, they had been sold to NTA and Republic Pictures. I tried to access those films for probably three or four decades. I was never able to get them until, by some miracle, Republic’s library got sold back to Paramount Pictures where they were originally made.

A Hatful of Dreams (1944 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

Now Paramount is working with me hand in hand to help preserve and get more of the films done. As they come from the negatives the quality is just mind-bogglingly beautiful, you would think they were made yesterday. The reason for that is because they are scanned directly from the successive negative, there’s no intermediary generational film prints so you’re looking right at the negative in technicolour, in three strips – and no one has ever seen them look that way. In terms of quality it’s a great accomplishment because none of the other films, except for those at the BFI, have original negatives; a lot of the other archives have prints. It’s been an amazing journey, this whole thing was an accident. I made the Puppetoon Movie thirty five years ago, I had moved on to other things and then I heard some of these films started turning up in Europe and knew we had to get the rest of these done.

I was really excited to see Wilbur the Lion as I had read it was quite hard to find. Can you tell me about finding that film?

I wanted to have Wilbur in the original Puppetoon Movie when I did it, but it didn’t exist. There were no prints, Mrs. Pal didn’t have any copy, I searched everywhere and it just wasn’t available until about six, seven years ago, I was on the phone with a collector talking about other things and it happened to come up in a conversation! He says, “Oh, I have a 35 millimetre print of Wilbur the Lion, a nitrate”. I fell off my chair and I said, “Please, can I see it?”. So he donated it to the Academy and told them to give me permission to get access to it. That, as far as I know, is the only nitrate print that exists. Maybe Paramount has the successive negatives of it, so it could potentially be restored from the successive negative, but I’m not sure.

Wilbur the Lion (1947 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

Every now and again you see some of his original puppets turn up at auction or personal collections, there must have quite a lot of physical material produced due to the process. Other than the films themselves have you come across much in the various archives of the pre-production materials, such as scripts, puppets, and designs? And is there a plan to do anything with these?

There’s not much – they were mostly sold off. George was a very generous person. He gave away many of the puppets as gifts to people all over the world that had them in their collections. The big problem, which is a tragedy, is there was a fire that happened in his Bel Air house in 1962. Mrs. Pal told me everything burned to the ground. A lot of the original artwork, and many of these materials went up in that fire.

Love on the Range (1938 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

I have a few things myself that Mrs. Pal has given me. Some scripts, some books, and a few other things. I mean, they’re priceless as far as I’m concerned, I don’t let them out of my sight. But I would say if anyone’s interested, they would have to go to the Academy and see what they can find. They could also check with UCLA Film Archives.

The sheer craft and quality of his work is phenomenal, can you explain his process and why it was such a game-changer for animation production?

The things he did you can’t possibly even consider replicating. It’s almost insane. The way that story goes, he was a cel animator and was so bored of drawing that he came up with the idea of using three dimensional objects. He had a cigarette in his hand and said, “What if I use this?”, so he called the sponsor and asked what they thought of using their own cigarettes with the trademark on every frame. The sponsor loved the idea. So then he started animating cigarettes to the music. Eventually, he put heads and mouths on so they could talk, legs so they could walk. So he basically took his flat cel animation and put it into three dimensions.

Pal’s big idea was replacement puppets, the idea where every frame of film is essentially a separate puppet or puppet part. He made thousands of puppets out of wood, which is extraordinary when you see them stretch and move. George basically pre-constructed and pre-designed everything before it was ever shot. Everything that Pal did, he did in his head before and he laid it out on these elaborate directors’ sheets, where he would write and draw every move of the puppet, every leg, every head, every move, every stretch – a different construction was made for every single frame of film. It was just an enormous amount of work.

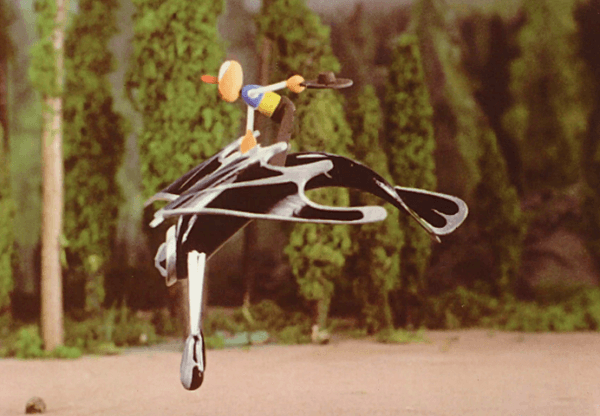

Sky Pirates (1938 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

The animators couldn’t believe what Pal had done. I’ve heard this story from Ray Harryhausen, Gene Warren and other people that worked on the Puppetoons, that Pal thought that it was a good idea because he could get almost anyone to animate, so he could hire a young animator who had never animated before, show them the sheets and they would basically be following the numbers, so to speak. It wasn’t easy for the animators, they went crazy in those early days, some of them wanted to kill each other – or him – because it was so tedious and difficult, I think. Eventually, over time, the animation started to expand and simplify, using less puppets. Eventually, a single puppet was refined and became the armature puppet because the animator wanted to have more expression in the animation itself. But nothing comes close, as you said, to the fluidity and the style of those replacement animations because it’s in real time, three dimensions, single shot, frame by frame, with no cheating, no double or triple frames. It’s somewhat stunning to see, even today.

I think because it had never been done before. George was a pioneer. He was an innovator. He was an original thinker. You don’t find many of those in the history of the world. I would say he was way ahead of the game. He was the one that generated the ripple effect that went on and on through history with so many other people.

Pal has a huge body of work and clearly had a big influence on the history of animation. His influence can be seen in the work of many over the years including studios like Rankin & Bass and Laika. Could you tell me a little about Pal’s contribution to stop motion as an art form and why you personally find his animated works so appealing?

I think it’s the stylization, the believability of the character. There’s a certain comic quality, they have a lot of humour to them. It just feels believable to me in a way that feels real. When I watch CGI, it feels cold to me, it doesn’t feel real. When (Disney) made Nightmare Before Christmas, they had me up to the studio and I was there when they shot the film. Tim Burton was a huge George Pal fan, so when I went into the modelling shops I met all the animators and model makers and in the room, and they’re making sequential puppets. So I saw that Nightmare was basically a Puppetoon.

The Gay Knighties (1941 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

Today everybody thinks they invented everything, but the style of the Puppetoons, the fluidity, the movement that came about from the wood puppets, everybody tries to replicate it, but you can’t. It’ll never look that way. CGI has its limitations. You can create all the things you want but there’s something about real life, three dimensional animation. You’re taking a camera in reality and you’re shooting a single frame at a time, which gives real depth of movement with no breaking up of the movement. You’ll notice in things like Rankin and Bass but also things like Davey and Goliath or Gumby, they don’t have that fluidity that the Puppetoons have. Even Ray (Harryhausen) didn’t do everything on ones when he did his animation. Sometimes it was on twos and later on, on threes because it was too much work otherwise.

Two-Gun Rusty (1944 – Image courtesy of Arnold Leibovit)

I think Jim Danforth is amazing, he’s one of the great designers and animators in my view, and he’s got that George Pal skill. His animation is very fluid, it’s very smooth, it doesn’t stagger, it feels very believable. I know animators today that are trying to do it, they all go back to Pal and look up to that as a sort of template, they’re trying to replicate it, you see, they’re limited by budget, time and design. Everything gets crunched down – time, money and a lot of other factors that restricts them from making it the way they want.

So there are some realities to it, unfortunately. So it’s a window into the past, journeying back to a time of magic and wonder, getting a picture of something that is a total miracle, something that is so unique, so special, so inspirational, that it almost becomes revelatory. It will always remain that special piece of magic that existed in the past. That’s the feeling you get when you see the Puppetoons, that childhood wonder – that was George’s gift to the world.

So you’ve created a film, a documentary and now two Bluray collections of his work, what is the plan for the future?

I’m trying to build more support for this current volume. There is a core group of fans who are very excited but I need the funding and the support to be able to do the third volume, which is already in the works. I already have several films being restored, which is a very long, time consuming process. Paramount is preserving a few of the successive negatives for me now, which is absolutely amazing. I can’t wait for people to see these new ones that have never been seen before.

The Puppetoons Movie Volume 2 is available to UK customers via eBay (UK) and from puppetoon.net (US/rest of the world). To donate and learn more about Volume 3 visit puppetoon.org/vol3